The paper bag solution is the crux of a story arc in The Wire. It is a bright idea against the futility of the drug war policing espoused by one of the prominent characters of the show from the third season on, Major Howard (Bunny) Colvin.

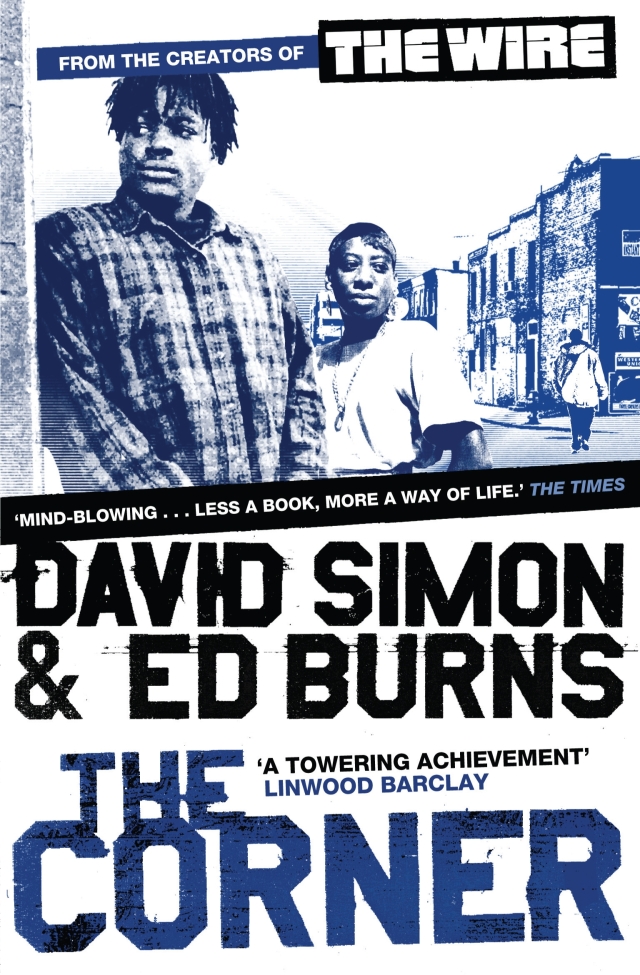

The names and the details and the characters themselves are not central to the point here. The idea itself originated from the book The Corner, by David Simon and Ed Burns. The writing is beautiful, stark and probing, as you would soon read. It is an observation of real life, the details of human characters and institutions and the city blending in and out of the narrative in an honest, non judgmental gonzo voice. But that is again not the point.

Everyone knows about the drug war, the government’s position, the futility of all preventive actions, and yet this writing doesn’t let you in on the idea easy. The narrative emotively builds up to the idea by getting you around the corner first, getting one familiar with the Corner through eyes like Fat Curt’s, and the best beat police officer you would want for the discussion, Bobby Brown. So it gets you emotionally involved, intellectually alert, then greets you with the statistics and the futility of the current course of action, and the why of each. The Wire picked it up from here taking this idea, the paper bag solution, and giving it to a major character, and letting him run with it, to it’s logical end conclusion.

I can’t appreciate that point enough. Lots of us have bright ideas, about games we are in, and about games we know nothing about. We all feel we can give a pointers or two about games because we have had those ideas, and can justifiably feel above the rot, and better than the afflicted. And yet, people like me give up after a very shallow understanding of the scenario.

Why is there crime on the streets?

Because the police aren’t doing their jobs.

Why aren’t the police doing their jobs?

Because the political class benefits from crime, and has control over the police.

Why does the political class benefit from crime? Why is their no independent will of police, or politicians? Why can’t there be good police or good politicians?

Oh fuck it.

That is where my thought process stops. Moreover, at each of those stages, I made the glaring presumption that the police, the politicians, all other institutions don’t WANT to do their jobs. That there are bad cops and bad politicians and bad junkies. And how did I presume that? Because the problems are not solved.

If there were good cops or good politicians, policing and governance would not be fucked up. Right?

Wrong.

This is where The Wire as a simulation of the real life problems facing our cities, and us as seemingly smart, logical, emotional beings navigating through it together transcends any other example which I can think of. It is this Socratic method that David Simon employs with The Wire of continuing with Why, Why, Why along that logical ladder to find out why things don’t work out as simple as thinking idea applied becomes solution. Why it is wrong presuming that the problem is with correct intentions instead of a systemic rot and bottleneck in processes.

[I can’t help but compare this simulation with Richard Dawkins explanation of the evolutionary development of thought in The Selfish Gene (about which I shall hopefully soon write). He says that all thought is simulation for possible scenarios in life. All evolution (and hence the tendency of the natural world) is towards survival and if simulation helps genes survive, such processes that promote development of thought in organisms would be encouraged. (He goes on to say “Consciousness develops perhaps when your simulation of the world also includes a model of yourself”, an excellent thought when thinking of The Wire as higher consciousness)].

There is no mention of Major Colvin in the narrative below, there’s no character of that name here. This being a blog, I could easily have cut right to the idea for easier readability, but that would be losing the beauty of the narrative. However, I have highlighted in bold where the paper bag idea starts in the writing below. But enough with this long winded introduction, here you go with this extract below from the book The Corner. Read this and tell me how any fictional depiction could rival this, reality?

“He’s back,” says Fat Curt, caning away.

“Damn,” says Pimp. “I ain’t even had the chance to get lonely for the man.”

Curt laughs softly, and the two old friends beat feet toward the mouth of Vine Street. Grizzled and worn, Scalio is waiting there, a look of growing discomfort on his face.

“You seen him?” he asks Curt.

But there isn’t a spare moment in which to answer. Just then, the man himself comes cruising around from Lexington, grimacing behind the wheel. Scalio sags at the sight.

“Shit,” he says, falling in behind Curt and Pimp, “they gave him the wagon.”

At Fayette and Monroe, there is no sight more unwelcome than that of Officer Robert Brown, back from his vacation, laying hands upon the sinners and working the silver bracelets hard. He leads this afternoon’s blitzkrieg from the driver’s seat of the Western District jail van. Bob Brown and his lockup-on-wheels.

“What day is it?” asks Bread.

“Today Tuesday,” says Eggy Daddy.

“Zebra Day,” says Bread, with finality.

The others nod in agreement. Zebra Day is the blanket corner explanation for anything involving drug enforcement in West Baltimore. If it carries cuffs and a nightstick and hits you hard, it’s got something to do with Zebra Day.

“Where he at?”

“Gone down Fulton and round the block.”

“Aw shit. Bob Brown comin’ through.”

The patrolman grabs a tout down at Gilmor, then wheels up to Lexington and rolls the wrong way around the corner at Fulton Avenue, coming up on the Spider Bag crew, where he grabs one of the lookouts. Then down to Fayette again and up the hill to Monroe, where he takes off a white boy trying to cop outside the grocery. Then down to Payson and back up Lexington to Monroe, where he grabs one of Gee’s workhorses.

“Bob Brown collectin’ bodies.”

“Best move indoors.”

Slowly, the corner crews drift off Monroe Street, moving through the back alley between Fayette and Vine, slipping through the minefield of trash and broken furniture until they’re at the rear of 1825 Vine. They can’t help but see Roberta McCullough framed in the rear kitchen window. Though most manage to avoid eye contact, some of the older heads try to be neighborly.

“G’mornin’,” says Bread, waving.

And Miss Roberta, unsure, simply returns the wave.

That the shooting gallery has moved from Blue’s to the rowhouse adjacent to the McCulloughs is no surprise; since Linda Taylor caught the Bug and died in January, ownership of 1825 had settled on Annie, her daughter. Already on probation from one drug charge, Annie was doing little more than waking up every morning and chasing the blast until she fell into bed at night.

And make no mistake: Rita and her patients caught a real break when Annie decided to open her house to them in the dead of winter. After all, there was no heat or running water in Blue’s, and since Blue had been locked up, the fiends had stripped out all that was left of the furniture and most of the windows. By contrast, Annie would open the kitchen oven for warmth that could be felt throughout most of the first floor. And while Rita worked the candles and cookers at the kitchen table, the front room served as the lounge, with the regulars stacked up on what was left of an L-shaped sofa arrangement, all modular and maroon and looking like it belonged in the lobby of a Ramada Inn.

For the McCulloughs next door, the decline and fall of 1825 represented more than the daily irritation of nonstop drug traffic; that much was a given with crews already slinging at either end of Vine. For W.M. and Miss Roberta, a shooting gallery next door meant living with the possibility that they would wake up at three in the morning to the smell of smoke and find their Vine Street home and a half-dozen others ablaze. The McCulloughs could watch the foot traffic and imagine dozens of addicts stumbling in and out of that worn, wood-floor kitchen next door, dropping matches and knocking over candles. Any night now, Annie’s crew might burn half the street out of doors.

The McCulloughs could call the police, of course; Miss Roberta had thought about that. But then again, she had seen how many times the police had run through Blue’s and boarded up the place, only to have the fiends pull off the plywood and start over again. And what if Annie and her houseguests found out that the McCulloughs had called in on them, or even mistakenly believed that the McCulloughs had done so? If the police did come, it could mean more trouble than help. No, there was nothing to do but watch solemnly from the kitchen window, hoping against hope that Annie might pull herself together and tell the circus to move on.

Today inside 1825, the regulars warm themselves at the stove door and wait for Bob Brown to fish his limit. Bread, Fat Curt, Eggy Daddy, Dennis, Rita, Shardene, Joyce and Charlene Mack, Chauncey from up the way, Pimp and Scalio—all of them lazing around the first floor, waiting on Mr. Brown.

“He comin’ back down Vine,” says Scalio, peering at the edge of the front shade.

Annie moves toward him, muttering nervously. “You should come back from the window,” she warns. “He gonna see you signifyin’.”

“He ain’t see shit,” says Scalio, watching the wagon disappear at the east end of Vine. He moves to the door, cracking it enough to see Bob Brown’s jail van turn north on Fulton. Heading back up to the Western, maybe. Going to the lockup with a wagonful.

“Motherfuckin’ Bob Brown,” says Charlene Mack.

“He too evil,” agrees Bread.

Scalio goes outside, paces cautiously for a minute, then starts walking back up to Monroe. Down the block the Spider Bag crew is trying to set up their shop, the touts seemingly indifferent to the loss of their lookout. Pimp and Bread slip out the back door, then come back moments later with news.

“Death Row puttin’ out testers.”

In a heartbeat, the house is emptied of fiends, save for Rita, who stays in the kitchen, poking at the raw flesh of her left arm with a syringe. Two minutes more and a half-dozen of them are back, stumbling through the back door, winded from the run.

“You was quick,” says Rita.

Bread snorts derisively. They didn’t even get across Fulton before Bob Brown rolled down Lexington. And not just the wagon alone; Mr. Brown has a two-man car following him. The girl police, Jenerette, and that new white boy, the one with the marine cut.

“They just snatchin’ niggers up,” moans Annie.

“Zebra Day,” says Eggy Daddy.

It’s a timeworn phrase on these corners, dating back to the late 1970s, when some tactical wizard in the police department reckoned that the drug war could be won by alternating between East and West Baltimore and sweeping the corners clean at the rate of twice a week. Mondays and Wednesdays on the east side, Tuesdays and Thursdays on the west side, with Fridays off so the police could get a jump on their weekend—that was the Zebra schedule. On all other days of the week, the West Baltimore regulars might be subjected to ordinary law enforcement, but on Tuesdays and Thursdays, all bets were off and anything might happen. Knockers, rollers, wagon men, plainclothes jump-out squads—every spare soul in the police department seemed to be lighting on the corners. On Zebra Day, a routine eyefuck that might otherwise be ignored by a patrolman would buy a Western District holding cell, just as a routine insult would often result in a mighty ass-kicking. And on Tuesdays and Thursdays in West Baltimore, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were largely without meaning. On Zebra Day, there was no such thing as probable cause; any police could go into your pockets by invoking the Zebra logic.

Of course, it was all myth. The years had passed and the corners had grown and the once-awesome spectacle of Zebra Day had become merely a trace memory, the Baltimore Police Department having moved on to new tactics and new slogans. These days the corner regulars invoked the voodoo incantation of Zebra Day more than the police ever had; even thirteen-and fourteen-year-olds—born after the advent of the original Zebra—were still citing it as explanation for whatever events happened to occur on those days. Like today, a Tuesday in March, when Bob Brown is pushing the jail wagon, harvesting the corners, moving the sullen herds to and fro like some saddle-assed West Texas cowpoke.

Must be Zebra.

Peeking out of Annie’s front door, Eggy Daddy watches the top end of Vine for a few minutes more and, sure enough, the wagon makes the turn from Monroe, rumbling down the gentle slope of the alley street. Vine is empty now—Bob Brown has succeeded in momentarily chasing the crews indoors—but still the man is on an angry tear.

“He just all mean and miserable and a motherfucker,” says Charlene Mack, ascending to alliteration. “One day, someone gonna hurt him.”

Grunts of affirmation all around.

“Someone gon’ put a bullet in his ass,” says Eggy.

Someone, someday. Along Fayette Street, they’ve been saying such stuff about Bob Brown for twenty years, talking for two solid decades about a reckoning that never seems to come. Long after the rest of the police department has conceded the Fayette Street corridor to drug trafficking, Bob Brown is still decidedly undefeated. Long after every fiend in an eight-square-block grid wished him dead and gone, Bob Brown is still clinging to the real estate in eight-hour-shift installments. It’s sad and comical, but in some way genuinely noble: Bob Brown, walking the beat or riding that wagon, trying to herd the pigeons, trying to rake all the dry, brittle leaves into a pile on a windy day.

On one level, they hate him for it. Hating Bob Brown is an obligatory act for every fiend in the neighborhood. But at the same time, the souls on the corner allow a grudging respect for Mr. Brown and his game. If nothing else, the man is consistent, a moral standard in a place where it’s increasingly hard to take measure of morality. He can be brutal, but at the least he is consistently brutal, resorting to violence only when there is some justification for it. And when Bob Brown turns a corner, the odds are exactly the same for everyone. If he says get, you get or you go to jail. If he wants to go into your pockets, you put your hands against the liquor store wall and let him search, because there is no point in running from Bob Brown. If you run today, you’ll have to come back to the same corner tomorrow, and then, as sure as night follows day, there will come a reckoning. And if Bob Brown, while knocking you on your ass, decides to call you a low-life motherfucking piece of shit, you are—at that moment, at least—a low-life piece of shit. At street level, there can be no arguing with the man.

Even those who want Bob Brown dead have to acknowledge that it isn’t racial. Oh yeah, Mr. Brown is big and white and nasty, and every once in a while, on a day when he is truly pissed off, he might even let go of an epithet. But the Fayette Street regulars have lived with Bob Brown for years now; they’ve seen how much abuse he’ll readily heap on the white boys he catches creeping north out of Pigtown, venturing across Baltimore Street for a chance to hook into a better product. In their hearts, they know it isn’t race; it’s much more than skin-deep.

Bob Brown hates everybody, they are quick to assure you. And then, later, they think on this and realize that not even a police as mean and miserable as Mr. Brown can muster hate enough for everyone. Bob Brown doesn’t mess with the ladies up at St. Martin’s, or Miss Roberta, or Miss Bertha, or the people out at the bus stops going to work in the morning. No, when pressed, they have to admit that Bob Brown is not quite so unreasoning.

“He just death on drugs,” says Gary McCullough, watching from the steps in front of Annie’s as Bob Brown and his full-up wagon bounce around the corner and turn on Lexington.

“That’s what it is,” agrees Tony Boice. “He don’t like dope fiends even a little bit.”

On the corners, they tell themselves that it’s more than police work, that it’s something that happened to Bob Brown, or maybe to someone in his family. His first wife got addicted and turned out by her supplier, some claim. Not his wife, others argue, but a younger sister, who came up an overdose back in the seventies. The exact details have never been nailed down and, absent facts, such apocryphal stories become more melodramatic with each telling: Bob Brown grieving for lost loves and wasted relatives, swearing to make generations of Fayette Street fiends pay the price for some deep and painful family secrets. Out on the corner, only the worst kind of scenario could explain the angry timelessness of the Bob Brown Crusade.

The other police are different—more reviled, in some cases—but different nonetheless. Most no longer even pretend that they are trying to hold or reclaim their posts from the ceaseless drug trafficking. Instead, the best of them are content to harvest the comers for a quota of street-level arrests, a small sampling of lawlessness that will always prove as meaningless an act of enforcement as it is random. The worst of them have lost themselves in the siege mentality of the drug war, giving back to the corners the same hostility that greets them. Fayette Street for them is a place deserving of Old Testament justice: an eyefuck for an eyefuck, with handcuffs for minor insults and lead-filled nightsticks or slapjacks for any greater provocation. The new breed of police along Fayette Street—Pitbull and Shields, Peanuthead and Collins—has no feeling for the pavement on which they are warring, no sense of a communal past by which the present might be judged. For all of his bluster, Bob Brown carries that burden.

In that regard, Bob Brown is what every police official and neighborhood association claims as the solution to the trouble in their streets. He is every bit the old-time beat cop, the retrograde image of walk-the-footpost, know-the-people policing. Get the cops out of the radio cars, runs the latest theory, and you begin to get them back into the neighborhoods. Get them out walking their real estate, and they’ll start to reconnect with the people, learn the neighborhood, prevent crime. Community-oriented policing has become the watchword of the nineties in law enforcement. Houston, New York, Washington, Detroit—everyone is nostalgic for foot patrols and grassroots policing and whatever the hell else kept the streets safe in 1950. That Bob Brown knows his post from one end to the other, that he can recite most of the players and their deeds by name, that he has fought for the same terrain for two decades—all of it seems the textbook model of what the visionaries in law enforcement are promoting. That there are already Bob Browns on the streets, that for all their will and desire and knowledge, they have lost their private wars in hardcore places like West Baltimore—that is somehow beside the point.

And lost it they have. On Fayette Street, Bob Brown has fought tenaciously, clearing corners, herding fiends, chasing slingers, and arresting hundreds every year. Yet he has watched helplessly as the rot from the vials and glassine bags rolls upslope from the housing projects and down across the west side expressway, reducing the working-class neighborhood where he began his career to little more than a collection of open-air drug markets and crumbling shooting galleries. He’s witnessed a couple generations of young girls having their babies, then watched as those children were named and nicknamed, diapered and raised. And he’s been there when those children began their inexorable drift away from the schoolyards and ball courts, when they started to play at the fringes of the corner. Unlike so many of the younger police, Bob Brown knew many of the fiends before they ever chased a blast, many of the slingers before they went to the corner with that first stepped-on, scrambled package. More than any other cop working Franklin Square, he can bring names and faces and family histories to the history of disaster, and now, with the neighborhood in chaos, he bears witness as the dope-and-coke tide crests the hill at Fayette and continues south across Baltimore Street, down into Pigtown and Carroll Park.

Down there, the hillbillies aren’t proving to be any different; there are all-white and even some integrated crews selling coke all along McHenry Street, dope down at Ramsay and Stricker. The decay in West Baltimore is unremitting, epic; to police against it, you need either the quixotic rage of a crusader or sense enough to detach yourself from the totality of the nightmare, to hump your share of calls and make some cases and then grab that twenty-year pension.

The sad beauty of Bob Brown is that he shows no sense whatsoever. Against all evidence, he is still crusading, still defending a neighborhood at a time when the threat is from the neighborhood itself. For Mr. Brown, the question is the same on any day that he walks from the Western District roll-call room to a radio car: How do you make police work matter when more than half of Fayette Street, perhaps eighty percent of those between the ages of fifteen and thirty, is in some way involved in the use or sale of heroin and cocaine? To be sure, there are still citizens in Franklin Square: older men who still call 911 or 685-DRUG to provide information about the trafficking; women who let Bob Brown into their houses so he can peek from behind the drapes and watch slingers serving up in the alley. Still for every one of those embattled souls, two or three others are going to the corner.

Yet he endures. Like today, when he’s dragging that jail wagon around the corners, filling it with a half-dozen of the prevailing herd—and all but one of them locked up as humbles, charged with failure to obey, or disorderly, or loitering in a city-designated drug-free zone (“where drugs are free,” joke the sages and touts). The last of the unfortunates has gotten himself caught with a handful of vials, but no matter—all of them are going to disappear for a night, or a week, or a month at the most. And as Bob Brown finally tires of the chase and turns the wagon north on Fulton Avenue, heading toward the district lockup, the corners come alive again.

“Shop open,” says Hungry, sliding out of Annie’s.

The crews on Fayette and Vine Streets step gingerly back into the mix, one eye on the game, the other on the far corners, still nervous about seeing the motorized Mr. Brown making another pass. Back at Annie’s, Rita takes a rest in a broken-backed kitchen chair while Annie peers out the front window, worried as always, thinking that it’s her that they’re looking for. Her and her house. Thinking that they’re all out there—Bob Brown and Pitbull, Collins and Shields—wondering where the regulars from Blue’s have gone. Wondering which door they’ll have to kick in next to find the needle palace.

“I’m on probation already,” she says sadly.

She nurses such fears alone. The rest of them are there with her, but thinking no thoughts about anything beyond shooting dope, shooting coke, and staying warm. They’ve found a home and they know that as long as Annie gets her share of the hype, they’re going to be firing drugs and nodding off in a heated room with running water. With any luck at all, they’ll be at Annie’s until the March winds give way to April and true spring. By the standards of shooting-gallery life, the regulars from Blue’s are fortunate indeed.

It seems that way for a week or more until a fresh crew of New Yorkers sets up shop at Lexington and Fulton and begins selling some Black Tops of coke that are an absolute bomb. Before long the morning tester lines are stretching across the vacant lot at the bottom of Vine Street and the alley itself is filled with drug traffic. Annie’s refuge is suddenly in the center of the action, and the police seem to be snatching bodies off Vine Street on a daily basis. Sure enough, it isn’t long before one of the white boys from McHenry Street gets spotted after hooking up with some Black Tops on the vacant lot. The boy makes the mistake of trying to run with Pitbull chasing him; worse, he makes the mistake of trying to lose himself by running through the alley and up into Annie’s kitchen door.

“Not in here, fool,” yells Shardene.

But it’s too late. Pitbull is right on the kid’s heels, kicking through the warped wooden door and charging across the threshold with the back-up troops only a few seconds behind him. He grabs the white boy in the front room and slams him against the flaking plaster wall, punching him twice for luck. Out come the cuffs, with the white boy moaning and begging and Pitbull telling the kid to just shut the fuck up.

The other troops have everyone jacked against the wall, waiting, the room strangely silent in the wake of what amounts to a warrantless raid. On the kitchen table are Rita’s candles, a plastic tub of dirty water, and a half-dozen syringes. Scattered around the room is a who’s who of Fayette Street regulars, and when the rest of the occupants are ordered down from the second floor, it’s a veritable convention.

“Look at this shit,” says one of the younger police.

Leaning against the maroon sofa, Annie closes her eyes and waits for tears that won’t come. She’s lost her house, she figures. They’ll bring the city work truck and board up the doors and windows, and she’ll be out on the street with the rest of them. She might even take a charge, and that would mean a couple of years backing up on her, since she walked away from an Excel detox program, violating her last probation.

And yet, incredibly, after Pitbull drags the white boy out the front door, the other patrolmen follow him, leaving the fiends where they stand and the shooting gallery in place.

“They comin’ back?” asks Hungry.

Annie stares through the front blind as the white boy is dragged to the wagon. Finally, she shrugs.

“Don’ know.”

“Well fuck it then.”

The police stumble into a shooting gallery, the police leave the shooting gallery; the party goes on. It’s a telling moment, a wake-up call for anyone along Fayette Street who still believes in an urban war on drugs. But no one in Annie’s had any clue what to think until it happens again a week later, the cause on this second occasion being Bread, who’d been running and gunning at flank speed all month, chasing those Black Tops and slamming them home one after the next. They’d all been going at the coke heavy—Curt, Bread, Dennis, Rita, the whole crew—a celebration of sorts to mark the end of winter. They’d soldiered the hard months; now, there was a scent of easier times in the air, a hint of their just rewards for having struggled through so many twenty-degree mornings on the cold floor of Blue’s empty vessel. But Bread had been twenty-four, seven on the strong coke, not even taking time out to crawl into his mother’s basement door and sleep a morning or two away. When he did crash, it was on Annie’s sofa or in one of the battered bedrooms upstairs. All of them were soldiers, but Bread had become the Viking.

So when he finally falls out, no one pays it much mind. He stays in the front room, slumped in a heap on the sofa, his winter coat under him, his breath coming in rasps and wheezes. He tosses fitfully for a few hours, then begins mumbling in a half-sleep, telling unnamed and unseen adversaries to go away and let him the fuck alone. Then his breathing becomes more erratic; Annie, watching from a chair in the other corner of the room, is unnerved to see her friend open his lids wide for a moment. The eyeballs have rolled up inside his head.

“Bread, wake up now.”

“NNNAAAA.”

“Bread … somethin’ ain’t right with Bread.”

They get someone at the McCullough house to call 911, then open the front door and wait ten minutes for the ambulance, with Annie stroking Bread’s hand and rubbing his head, telling him that help is on the way. But the paramedics can’t stabilize him; they can’t manage a steady pulse in a forty-six-year-old body that looks to be twice that old. They hit him with the Lidocaine and the steroids and whatever else they’ve got in the truck, but nothing seems to bring him up from the abyss. When two or three police come through to watch the paramedics, they again give the house a once-over, shaking their heads in disgust. Catching the scent of Rita’s rotting arms, one of the young patrolmen actually orders her into the bathroom, using his nightstick to poke her across the threshold as if she’s nothing more than viral.

“What did he have?” asks one of the paramedics.

“Huh?”

“What drugs did he use?”

There’s only silence.

“I need to know what he had. If you care about this guy, tell me.”

“Coke,” says Annie. “Coke and dope both.”

Once or twice, Bread seems to let out a moan, or maybe it’s just an explosion of air from his emptying lungs. When the ambo pulls off down Vine Street, his eyes are fixed.

The funeral is scheduled for Saturday up at Morton’s. Because it’s Bread, many of the fiends along Fayette Street make noises about going up there, if not for the services, then at least for one of the viewings.

Bread had been one of the originals on these corners, one of those rare few who had lasted long enough to make the consumption of drugs seem something like a career. His standing was such that rumors about his death swirl up and down Fayette Street, each a vain attempt to give the event more meaning than it deserves. Some hear that he’d been given a hot-shot by some New York Boys who wrongly thought he’d stolen a stash. Others talk about how he’d been firing some of that China White, the synthetic morphine substitute that killed about a dozen people in a single week last summer. Still others are whispering that they’d heard that Bread’s friends—lifetime companions like Fat Curt and Eggy Daddy—had panicked when they couldn’t revive him and had simply dumped the body in the back alley behind Annie’s house. In the end, the only rumor with any truth in it is the one that always follows a death on the needle: When the fiends along Fayette Street hear that Bread had succumbed to a blast of coke, they all, quite naturally, want to know who is selling the shit. Bread is gone, they reason, and that’s a shame. But that doesn’t mean the rest of us don’t know how to handle the good blast of coke that killed him. Come right here with that nasty shit.

Inside Annie’s, among the people who knew Bread best, there is a grief as sincere and heartfelt as for any taxpayer. Bread was of that earlier epoch when the corner life had rules, when there were standards that any self-respecting dope fiend had to consider. Bread had done twenty years around Fayette and Monroe, and to anyone’s best memory, he’d never cheated his friends, or fallen to violence, or intentionally damaged anyone other than himself. So Eggy Daddy promises he’ll be at the funeral. And Gary McCullough. And Annie, who cried the whole night through when word came back from the hospital that Bread didn’t make it, that he had all but died right there on her sofa. And Fat Curt, too—he surely wants to go up to Brown’s for the homecoming, though he hasn’t been able to bring himself to so much as speak about his friend since the ambo rolled away. For Bread, they all tell themselves, they’d surely step out of their game for a day and pay the proper respects.

But at five o’clock on the morning of the funeral service, the snow begins falling in thick, dry flakes all across Baltimore. By eight, there’s a foot of new whiteness on the ground and no sign of any break in the storm. On this day, the surprise blanketing—the only major storm of the year—transforms the corners of Fayette and Baltimore Streets, covering the trash and the discarded furniture, rendering uniform and pristine the usual scenery of broken rowhouses, corner stores, and vacant lots. The tester lines don’t form up this morning; the package is late. Even the police radio cars are off the roads, waiting for the city plows to go to work.

The regulars inside Annie’s figure that the service is canceled, or even if it isn’t canceled, they reason that there is no way they’re going to make it ten blocks north of the expressway in this kind of weather. More honestly, they look out the window and figure that it’s a day to make money with the blizzard slowing the police cars to a crawl.

And so, the corner gives up its dead to an empty funeral parlor, with Bread Corbett laid out in a Sunday pinstripe for his mother and a handful of other family members. The preacher, who declares himself a recovering addict, offers no cheap platitudes; he goes directly at the tragedy, speaking bitterly of wasted years and misspent lives. The family that hears him already knows the story; the family that doesn’t—the strange, extended clan in which Bread truly lived his life—is slogging through the snow on Vine Street, taking care of business. Only Joe Laney, sitting quietly in one of the back rows, is there at the end to say farewell. Joe had been on the corner with Fat Curt and Bread and the rest for years, only to pick himself up and walk away. He makes his way to Bread’s mother with his regrets.

“He was a good friend,” he tells her.

Two days later, spring is back in the air, the streets are covered in a dull, gray slush, and Annie’s is still the shooting gallery. After leaving with the ambo crew, the police have not been back, and it has finally started to dawn on some of the regulars that it isn’t about real estate anymore, that the police could care less. Up on the corner, Eggy Daddy is touting for the Gold Star crew, as is Hungry. Fat Curt is across the street in front of the grocery, his eyes yellow, his body bent against the warming breeze. He stands there, unmoving, with a thousand-yard stare on his face, one fat hand wrapped around a funeral parlor pamphlet, a token given him by Joe Laney. In loving memory of Robert E. Corbett reads the cover. The photograph is a high school graduation shot: Bread, circa 1965, in a dark sports coat and thin tie, deep brown eyes staring mournfully.

Curt pockets the pamphlet, but a few moments later, he takes it out and looks again at the photograph. This time, Bread. And before him it was Flubber. Cleaned himself up at the end and showed the courage to get up at those NA meetings and talk about having the Bug. First one to talk about it like that. And Joe Laney, now living a new life so that Curt only sees him when he rides by in that little car of his, heading up to his college classes. And House and Sonny Mays, both of them doing good, talking that NA twelve-step shit. And soon it will be Dennis, his own brother, dying by degrees, staggering around these corners as the virus chews him down to the bone. The fat man, ever more alone.

“Hey, Curt,” asks Robin. “Who that?”

Curt looks again at the old photo.

“Bread.”

“Got-damn. That Bread?”

“Back in the day.”

He’s still holding the funeral pamphlet, still looking at the ancient portrait through jaundiced eyes, when none other than Bob Brown turns the corner. Mr. Brown on the hunt.

Curt is slower than usual this time, distracted. He’s barely able to plant his cane and take a step before the patrolman is on him. Bob Brown looks directly at Curt, then down at the pamphlet in his swollen hand. Wordlessly, he steps past the aging tout, concentrating instead on a coterie of teenagers hanging by the pay phone.

“Corner’s mine,” he tells them. “Move.”

Curt wipes his eyes, then pockets the pamphlet. Slowly, he finds his step, but to no real purpose. The teenagers have moved off down Monroe Street, leaving two longtime veterans of Fayette Street alone for a moment on the corner.

“Hey,” grunts Bob Brown.

Then he steps past Fat Curt again.

The paper bag does not exist for drugs. For want of that shining example of constabulary pragmatism, the disaster is compounded.

The origins of the bag are obscure, though by the early 1960s, this remarkable invention was a staple of ghetto diplomacy in all the major American cities. And for good reason, since by that time virtually every state assembly and city council had enacted statutes prohibiting the consumption of alcoholic beverages in public. They seemed good laws, reasoned attempts to prevent rummies and smokehounds from cluttering the streets, parks and sidewalks; codified weapons to prohibit unseemly displays of human degeneration. That these goals might have been accomplished in small-town America, or in the manicured suburbs, meant nothing, of course, in the core of any large city. There, on the corners of the poorest neighborhoods, dozens of men would live their lives at the lip of a bottle of 20/20 or T-Bird or Mickey’s, public consumption law or no. Long before the open-air drug market, the corner was still the assembly point, the clubhouse; those who spent their days there couldn’t afford bar prices, but nonetheless preferred the corner ambiance to downing a bottle at home, particularly since home was more likely than not a third-floor walk-up with three screaming kids and a woman who hated you even when you weren’t drinking. No, it was always the corner.

For the police working these ghetto posts, the public consumption law posed a dilemma: You could try to enforce it, in which case you’d never have time for any other kind of police work; or you could look the other way, in which case you’d be opening yourself to all kinds of disrespect from people who figure that if a cop is ignoring one illegal act, he’ll probably care little about a half-dozen others.

But when the first wino dropped the first bottle of elderberry into the first paper bag—and a moment of quiet genius it was—the point was moot. The paper bag allowed the smokehounds to keep their smoke, just as it allowed the beat cop a modicum of respect. In time, the bag was institutionalized as a symbol; to drink without it was to insult the patrolman and risk arrest, just as it was a violation of the tacit agreement for a cop to ignore the bag and humble anyone employing it. In a sense, the paper bag allowed for some connection between the police and the corner herd; for the price of an occasional bottle, in fact, the smokehounds could often be relied upon to provide information about more serious matters. More important, the bag allowed the government to prioritize its resources, to ignore the inevitable petty vices of urban living and concentrate instead on the essentials. This is a truth once understood by any cop worth his pension—if you’re policing an Amish town and the worst crime is spitting on the sidewalk, then enforce that law. But if you’re policing Baltimore or a city like it, and the worst crimes are murder, rape, armed robbery and aggravated assault, then don’t waste your time, men, and money throwing gin-breathed wrecks into a police wagon.

But with no equivalent to the bag in the war on drugs, there can be no equilibrium on the corners, no accommodation between the drug subculture and those policing it, no relativity in the contemplation of sins and vices. Without the paper bag, animosity and, ultimately, violence are the only possibilities between the police and the policed, because there is no purpose to diplomacy or proportion when war becomes total. Granted, a paper-bag solution wouldn’t reduce the power of addiction, or steal any of the profit, or mitigate the disaster of a single life lost to narcotics; it is in no sense a cure for the drug epidemic. But there is still a priceless lesson in the idea, a valuable bit of beat-cop sensibility that could rescue both the patrolmen and their prey from their own worst excesses. No doubt some kind of war on drugs was a political inevitability, just as that war’s failure to thwart human desire was inevitable as well. But we might have saved ourselves from the psychic costs of the drug war—the utter alienation of an underclass from its government, the wedding of that alienation to a ruthless economic engine, and finally, the birth of an outlaw philosophy as ugly and enraged as hate and despair can produce—if we had embraced the common sense that comes with the paper bag.

Instead, as the addict population grew, we could see no connection between the corner rummy and the corner dope fiend. One was deemed a harmless, self-destructive soul, while the other was declared a sworn enemy. That some of those chasing heroin are genuinely dangerous is beyond dispute; the first wave of the national drug epidemic helped to fatten all the crime stats in the late sixties and early seventies. But the other side of that statement—the assumption that many of those chasing a blast are more a threat to society than corner drunkards—has been neither considered, nor argued. Even today, with cocaine added into the mix, the corner is in large part home to a tired collection of bit players, struggling to make their shot within the confines of the drug culture itself. Touts, burn-artists, doctors, slingers, stash-stealers, stickup boys who never rob a citizen, who only hit dealers, metal harvesters, petty thieves who grab a few dollars by shoplifting or breaking into cars, fiends who spend only what comes by way of a government check—shake them all out and what’s left to play the roles of predator and sociopath is maybe five percent of the population on any given drug corner.

Rather than target the truly dangerous, rather than concentrate on the murders, the shootings, the armed robberies, the burglaries, we have instead indulged all our furies. Rather than accept the personal decision to use drugs as a given—to seek out a paper-bag solution to the corner’s growing numbers—we tried to live by mass arrest. And what has been lost in our abject failure to make any legal or moral distinction between a corner victim and a corner victimizer is any chance to change the drug culture itself, to modify the behavior of those chasing a blast, to wean the worst violence from the corner mind-set, to draw those who might have been willing to listen toward ideas like community, treatment, redemption.

Instead, we have swallowed some disastrous pretensions, allowing ourselves a naive sincerity that, even now, assumes the battle can be restricted to heroin and cocaine, limited to a self-contained cadre of lawbreakers—the quaint term “drug pusher” comes to mind—when all along the conflict was ripe to become a war against the underclass itself. We’ve trusted in the moral high ground: Just say no.

We threw a negative at them, though it’s unclear what they’re supposed to say yes to on Fayette Street. We’ve made war against drugs in a social and economic vacuum, until hopelessness and rage have the damned of our cities fighting for nothing more or less than human desire and profit, against which no one has ever developed a single viable weapons system.

Thirty years after its inception, the drug war in cities such as Baltimore has become an absurdist nightmare, a statistical charade with no other purpose than to placate a public that wants drug trafficking attacked and vanquished—but not, of course, at the price it would actually cost to accomplish such an incredible feat. In Maryland such cognitive dissonance translates to a state prison system that can manage a total of just over 20,000 prison beds for prisoners convicted of every act against the criminal code in Baltimore and twenty-three other counties. Yet in Baltimore alone there are between 15,000 and 20,000 arrests each year for drug violations, and in all of Maryland’s jurisdictions, more than 35,000 are charged every year with drug sales or possession.

Build more prisons, you say? How many more? Five? Ten? Keep in mind that Maryland is no slacker when it comes to locking people up; the state ranks tenth nationally in its rate of incarceration. You could bankrupt the state government by doubling the existing prison space and still there wouldn’t be enough space to house the estimated 50,000 heroin and cocaine users in Baltimore, not to mention the rest of Maryland. And that leaves no room for those priority cases who just happen to be convicted of murder or rape or armed robbery. Moreover, the construction of a prison is only the preamble; what inevitably follows is the financial drain of staffing the place, of feeding and clothing the prisoners, of maintaining security standards, of running a medical program that the U.S. Supreme Court says must correspond to outside community standards for health care. Soon enough, you’re spending more to lock a man down than it would cost to enroll him at Harvard.

More prisons is the impulse answer, the quick-and-dirty response of so many hack politicians and talk-show hosts. It’s what the Bush administration told state governments to do as early as 1989 and what the federal government itself has done amid the escalating drug war. Leading by example, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons has doubled its capacity in ten years in an effort to keep up with a federal inmate population that is rising at record rates—the logical result of the mandatory sentences and parole restrictions contained in all those omnibus crime bills.

Yet even with more than 100,000 souls in federal custody, the U.S. prison population is only a tenth of the total number of those incarcerated. State prisons and state budgets are responsible for the rest. In the drug war as in every other aspect of law enforcement, the federal courts handle only the tip of the iceberg—the major offenders, the headline cases, and the crimes that happen to occur in federal jurisdiction. And here’s the rub: The U.S. government can happily build prisons into the next millennium because they don’t need real money to do it. As with everything else in the federal budget, prison construction and operation can be undertaken simply by adding to the federal deficit. State governments, meanwhile, carry more than 90 percent of the burden of incarcerating people and they, of course, must spend real dollars and balance their budgets.

So what happens in places like West Baltimore? What becomes of all those bodies thrown into the police wagons, all those man-hours of police enforcement, all the dollars spent on court pay and overtime, all that work for the courthouse personnel, the pretrial investigators, the public defenders and prosecutors?

Not much. In a typical year, the Baltimore police department and the assisting federal agencies will lock up a greater percentage of the city’s population for drugs than any other major urban area save Atlanta. The rate of arrest for drug charges in Baltimore will be nearly three times that of Los Angeles or Philadelphia, more than double that of Detroit or New York. In all, 18,000 or 19,000 arrests for the distribution or possession of drugs will be the usual result of a year’s police work.

Yet just as typically, fewer than 1,000 of those drug defendants will be sentenced to state prisons and, of that number, less than half will be sentenced to more than a year. The rest of the city’s drug docket will result in sentences of probation or dismissals. In short, for the vast majority of those arrested, the threat of incarceration is generally limited to a night or two in jail until a bail review hearing or, in the rare event that a money bond is set and a defendant is unable to pay, a month or two of pretrial detention.

It can’t be otherwise, because whatever prison space is available is required for the thousands sentenced every year for violent crimes and other felonies. The state judges have known this for years. The lawyers know it as well. So do the police. And the learning curve reaches all the way down to the corner itself: As early as 1991, 61 percent of the felony cases brought into Baltimore Circuit Court were drug violations, and of those, 55 percent involved defendants with at least one prior conviction. Thirty-seven percent had two prior convictions; 24 percent had three.

Up at the Wabash Avenue district courthouse, where arrests from half of the city’s police districts funnel into the judiciary, farcical scenes are played out on a daily basis. One morning after the next, the men and women of the corner flood the benches that line Courtroom 4, the Western District bench of Judge Gary Bass, a patient and beleaguered soul charged with making sense of this travesty.

One by one, the street-level drug cases—distribution, conspiracy to distribute, possession with intent to distribute, simple possession—creep off the docket and receive the only sanctions the state of Maryland can afford.

“… one year probation, supervised.”

“… continuing your probation for a year, subject to random urinalysis to be performed by the Department of Parole and Probation …”

“Six months’ unsupervised probation with the condition that you seek drug treatment.”

“… case placed on the inactive docket provided that you continue in your detox program …”

For Judge Bass, whose memory for faces is legendary, it’s a recidivist hell. On occasion, a defendant who is charged with something more substantial than drug involvement and is unwilling to risk a circuit court trial will catch a year or three for a breaking and entering, or for a handgun. And, every now and then, there comes a drug slinger so arrogant or incompetent that he shows up in court loaded with prior convictions and pending cases. For him, there’s a chance to slow down with a couple years at Hagerstown, which means parole in eight months or so.

At the federal courthouse, it’s very different, of course, because the national government, with its freedom from fiscal constraint, has cranked up the war as loud as she’ll go. The new mandatory sentencing guidelines can tag first-time drug offenders with five or ten years, just as the elimination of all parole assures that most of that time will be served. Yet by contrast to the state courts, the federal system is handling only a handful of prosecutions: those involving either major traffickers or minor players unlucky enough to get caught at the fringes of a major trafficker’s organization. The variance between courthouses has produced an institutional schizophrenia in drug enforcement. Fiends and smalltime slingers sometimes take three or four state charges, then get caught up in a case that goes federal. Suddenly, the man in the black robes is running wild, talking fifteen and no parole. Say what? Who changed the rules?

But federal sentencings are the odd, angry shot in this war. It’s at the local level that the endgame has been reached: There are now a million Americans in prison and it still isn’t enough to close the corners. Should we lock up a million more? Three million? The cost would be exorbitant. The death penalty for drug trafficking, then? The legal costs of killing a man by state decree are even higher than warehousing him for a couple of decades.

Meanwhile, out on Fayette Street, the absence of real deterrent has been factored into the psychological equation. As the cocaine epidemic has expanded the addict population, thousands more have flocked to the corners, and the drug slinging has become more brazen. There is still some cat-and-mouse with the police; no one wants to go to jail, even for an overnight humble, nor does anyone want to be among the unlucky handful who catch a three-year sentence from some dyspeptic judge. But in terms of real estate, the war is over; by the numbers, the drug trade has proven itself invincible.

In the drug enforcement establishment, the smarter players have caught the scent of defeat coming from places like Fayette Street and they’ve learned the vernacular of diminished expectation. No, we don’t see any light at the end of the tunnel. No, we don’t believe you can arrest your way out of the problem. The careerists in the Justice Department and the DEA, the top commanders in the nation’s largest police departments—most have learned to embrace the comprehensive view. The prevailing wisdom has drug enforcement as only one facet, with drug treatment and education as equal partners in some kind of global strategy. The smartest ones make it sound as if it’s really a plan, ignoring the fact that all their enforcement is driving addicts toward a wealth of government-funded treatment slots that don’t exist, and, let’s face it, never will exist in sufficient numbers. As for education, what we have is media saturation; all those this-is-your-brain-on-drugs sound bites have reached and convinced those willing to be reached and convinced. The inner cities have heard the gospel and ignored it.

Still, give the drug warriors credit: They’ve learned to incorporate enough seeming perspective to justify their budgets and grab for more. And can you blame them? What commander ever admitted that a war was lost until the absolute end was upon him? The DEA, Customs, ATF, the joint regional task forces, the local narcotics squads—all of them are feeding voraciously at the wartime trough, their operating funds coming not only from budget line items, but from the shared revenue of seized assets. They’re vested in this debacle. They’re a growth industry.

Yet who can argue with a moral war? If you give up, they assure us, It will be worse. And in one sense, they’re right: It will be worse in places where poverty is limited, where the demographics prohibit the growth of a ghetto underclass. Call off the drug war and it will be worse in Pittsburgh, or Kansas City, or Seattle. It will be worse in Nassau County, or Dearborn, or Orange County. In any place where the deterrent is still viable, where the lid is still being held down, a cessation of hostilities will result in greater damage.

But in West Baltimore and East St. Louis, in Washington Heights and in South Central Los Angeles—at the very frontiers of the American drug culture—it won’t make any difference. War or no, 20,000 heroin addicts and another 30,000 pipers are going to go down to the corner in Baltimore tomorrow. Save for the twenty or forty that get tossed in a jail wagon, not one is going to miss his blast. Against that fact, the drug war stands as a useless and unnecessary brutalization, an unyielding policy that requires our government to occupy our ghettos in much the same way that others have occupied Belfast, or Soweto, or Gaza.

True, a policy of repression was never the intent. But greater ideals are soon enough lost to the troops on the ground. For them, there is only the absolute futility of trying to police a culture with an economy founded on lawbreaking, of pretending to protect neighborhoods that can barely be distinguished from the corners that are overwhelming them. By the standards of a national drug prohibition, half of Fayette Street’s residents are deemed outlaws. As the radio cars roll past, they throw out their communal eyefuck, showing twenty-three-year-old patrolmen and twenty-six-year-old knockers what it’s like to be despised, to be regarded as an absolute enemy. For the younger police—the ones who never knew the neighborhood when it was worth protecting, the ones for whom the fiends were always fiends—there is no harmony, no connection to the streets or the people who live there. They are not serving anyone; they are answering radio calls and running up the daily arrests, pulling down that court pay for jacking up one or two souls a day. They learn to throw the eyefuck back at the corner, to be cynical, brutal, and sometimes corrupt. They learn to hate.

Gone are the days in Baltimore when the police didn’t get court pay for just any arrest, when they were judged instead by the greater standard of how they controlled their posts, when a beat cop culled information and tried to solve those genuine crimes that ought to be solved, when detectives still bothered to follow up on street robberies and assaults. Now, the worst of the Western District regulars have become brutal mercenaries, cementing their street-corner reps with crushed fingers and broken noses, harvesting the corners for arrests that serve no greater purpose than to guarantee hour after hour of paid court time at Wabash. And among this new breed of patrolmen are quite a few who are known by touts and dealers to be corrupt, who routinely keep some of what comes out of the pockets of arrestees. Win or lose, for them the war on drugs means pay day.

There’s a racial irony at work, too. By the late seventies and early eighties, a predominantly white police department acquired enough racial consciousness to be wary of the most egregious acts of brutality. But on the Fayette Street corners today, it’s a new generation of young black officers that is proving itself violently aggressive. A white patrolman in West Baltimore has to at least take into account the racial imagery, to acknowledge the fact that he is messing with black folk in a majority black city. Not so his black counterparts, for whom brutality complaints can be shrugged off—not only because the victim was a corner-dwelling fiend, but because the racial aspect is neutralized. Not surprisingly, some of the most feared and most despised Western District officers along Fayette Street—Shields, Pitbull, Peanuthead, Collins—are black. They seem to prove just how divisive and alienating the drug war has become, and how class-consciousness more than race has propelled the city’s street police toward absolute contempt for the men and women of the corner.

Take, for example, the notable career of David Shields, a black officer who was allowed to run up four brutality complaints in little more than two years, yet stay on the street all of that time. A few months more and Shields claimed his first body—a twenty-one-year-old slinger from Monroe Street whom he chased into an alley and shot, the fatal bullet striking the victim from behind. And though the police review of the shooting cleared Shields, there wasn’t a soul on Fayette Street who believed that the knife on the ground actually belonged to the slinger, or that the young man was dead for any other reason than that he had run from one of the Western’s hardest and angriest soldiers. Finally, when one of the brutality complaints was sustained by an internal investigation and Shields was hit with a civil suit for brutality against a Fayette Street resident, the department moved him to desk duties. Shields may be the extreme in the Baltimore department, but many of those policing Fayette Street—black and white—routinely go out of their way to show contempt.

Take Pitbull Macer, who one day stood in the middle of Baltimore Street with his hand around Black Ronald’s neck, choking the tired, yellow-eyed tout, demanding that he cough up drugs that, in this rare instance at least, Black Ronald did not have. And Pitbull, still unsatisfied, pulled out Ronald’s wallet and let the contents—ID cards, telephone numbers, lotto tickets—tumble into the street as confetti, then drove away, leaving the man picking his papers out of the street in absolute humiliation.

Or Collins, perhaps, who one afternoon got out of his radio car, took off his gun belt, handed it to a fellow officer and offered to kick the shit out of fifteen-year-old DeAndre McCullough because the boy had taunted him with a hard look.

“You gonna beat a boy,” Fran Boyd had yelled at him, shaming him back into the radio car, “and you a grown man.”

Or a nameless Southern District patrolman, the one Ella Thompson saw on Baltimore Street, who grabbed a sixteen-year-old on a loitering charge at Baltimore and Gilmor, then punched him in the face as the boy stood cuffed against the radio car. “The boy said something to him,” Ella recalled. “And he just knocked him down.”

To watch this younger generation of police is to get no hint of the sadness involved, no suggestion that the men and women of the corner are tragic and pathetic and, on some basic level, as incapable as children. In Baltimore as in so many other cities, the great crusade is reduced to a dirty war, waged by young patrol officers and plainclothesmen already jaded beyond hope.

And yet the war grinds on. Not only because the police and prosecutors are vested in the disaster, but because the entire political apparatus is at the mercy of public expectation. In Baltimore, the mayor and council members and agency heads hear it at every community forum, every neighborhood association meeting from one end of the city to the other:

“I can’t walk to the market anymore.”

“They’re out there on the corner twenty-four hours a day.”

“I’m a prisoner in my own home.”

Even along Fayette Street, where so many of the residing families are drug-involved, there is a vocal minority, a long-suffering network of old-timers still clinging to pristine rowhouses. They’re the tired few who show up at the Franklin Square community meetings, who come out to the candidate forums, who are still willing to believe that government, if it truly cared, could end their nightmare. And they vote.

What is a police commander, a city councilman, even a mayor going to tell such people? The truth? That it can’t be stopped, that the thing is beyond even the best of governments? Is an elected official going to stand up and declare that all the street sweeps, the herding of the corner pigeons, the thousands upon thousands of arrests have accomplished nothing in places like Fayette Street? Is he going to take the risk of admitting that for the sake of public appearances and a salve to our collective conscience, we are squandering finite resources on a policy that can never work?

The district commanders, the narcotics captains, the plainclothesmen—at every rank in the Baltimore Police Department, they still defend the prevailing logic, citing as evidence those beleaguered souls who show up at the community forums and demand action. These people are desperate, they tell you. They need help. We’ve got no choice but to chase the fiends, if only to give these people a break. So like clockwork, the government sweeps the corners and sends the bodies to Wabash. But in Baltimore, not only is the street-level drug arrest not a solution, it’s actually part of the problem.

It’s not only that the street-level drug arrests have clogged the courtrooms, devouring time and manpower and money. And it’s not only that the government’s inability to punish so many thousands of violators has stripped naked the drug prohibition and destroyed government’s credibility for law enforcement. More than that, in cities like Baltimore, the drug war has become so untenable and impractical that it is slowly undermining the nature of police work itself.

Stupid criminals make for stupid police. This is a stationhouse credo, a valuable bit of precinct-level wisdom that the Baltimore department ignored as it committed itself to a street-level drug war. Because on Fayette Street and a hundred other corners like it, there is nothing for a patrolman or plainclothesman that is as easy, as guaranteed, and as profitable as a street-level drug arrest. With minimal probable cause, or none at all, any cop can ride into the circus tent, jack up a tout or runner, grab a vial or two, and be assured of making that good overtime pay up at Wabash. In Baltimore, a cop doesn’t even need to come up with a vial. He can simply charge a suspect with loitering in a drug-free zone, a city statute of improbable constitutionality that has exempted a good third of the inner city from the usual constraints of probable cause. In Baltimore if a man is standing in the 1800 block of Fayette Street—even if he lives in the 1800 block of Fayette Street—he is fodder for a street arrest.

As a result, police work in inner city Baltimore has been reduced to fish-in-a-barrel tactics, with the result that a generation of young officers has failed to learn investigation or procedure. Why bother to master the intricacies of probable cause when an anti-loitering law allows you to go into anyone’s pockets? Why become adept at covert surveillance when you can just go down to any corner, line them up against the liquor store, and search to your heart’s content? Why learn how to use, and not be used by, informants when information is so unnecessary to a street-level arrest? Why learn how to write a proper search warrant when you can make your court pay on the street, without ever having to worry about whether you’re kicking in the right door?

In district roll-call rooms across Baltimore, in drug unit offices, in radio cars parked hood-to-trunk on 7-Eleven parking lots, there are sergeants and lieutenants—veterans of a better time—who complain about troops who can’t write a coherent police report, who don’t understand how to investigate a simple complaint, who can’t manage to testify in district court without perjuring themselves.

Not surprisingly, as street-level drug arrests began to rise with the cocaine epidemic of the late 1980s, all other indicators of quality police work—and of a city’s livability—began to fall in Baltimore. The police department began using more and more of itself to chase addicts and touts through the revolving door at Wabash and the Eastside District Court, so there were fewer resources available to work shooting cases, or rapes, or burglaries.

For the first time in the modern history of the department, rates for felonies began falling below national averages. In one six-year span of time—1988 to 1993—the clearance rate for shootings fell from 60 to 47 percent, just as the solve rate for armed robbery fell below 20 percent for the first time ever. Arrests for rape declined by 10 percent, and the percentage of solved burglaries fell by a third. Alone among felonies, the arrest rate for murder remained constant in Baltimore, but only because the high-profile aspects of such crimes prevented department officials from gutting the homicide unit as every other investigative unit had been gutted. In a department where competent investigators were once legion, the headquarters building was threadbare; the coming generation of police was out on the streets, running the corners, trying to placate community forums and neighborhood associations with an enforcement logic of sound and fury that signified nothing.

In those same years, the war on drugs failed to take back a single drug corner, yet the city’s crime rate soared by more than 37 percent to all-time levels. In 1990, the city began suffering 300-plus murders a year—a rate unseen in Baltimore since the early 1970s, when baby-boom demographics and the lack of a comprehensive shock-trauma system could be blamed. Baltimore became the fourth most violent city in the nation, and its rate of cocaine and heroin use—as measured by emergency room statistics—was the worst in the United States. By 1996, the cumulative increase in the city’s crime rate was approaching 45 percent.

In time, fewer and fewer of those living near the corners were fooled. On Fayette Street, those paying attention had lived with the drug war and the drug culture long enough to discern the range that separates sin and vice. To them, it said something that the kid who had shot three people this month was still on the street, or that the crew that had been breaking into area stores and churches was at it again, hitting the Apostolic Church on Baltimore Street just this week. It said something that the stickup crews were working Fulton Avenue and Monroe Street with impunity, that no one bothered to even report armed robberies anymore because they knew there would be no follow-up investigation. And it said something, too, that the only police activity they did see all week was down at Mount and Fayette, where the Western District day shift was, yet again, rounding up a handful of the usual suspects.