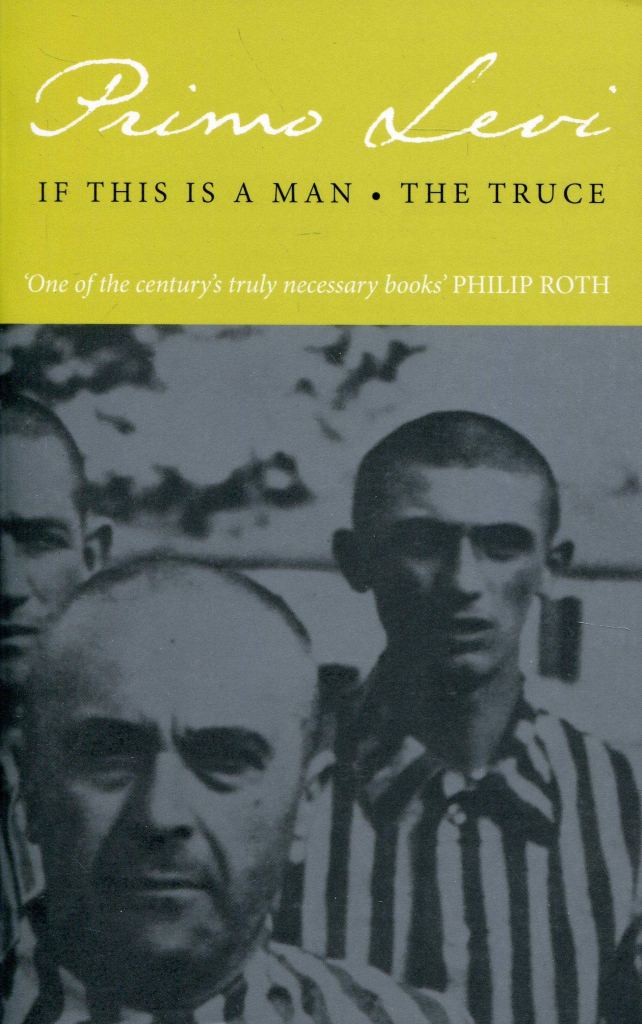

Primo Levi is a deeply unsettling writer. In the pantheon of Holocaust literature, Primo Levi’s voice is uniquely different (not for the obvious reasons). He is unsettling because he doesn’t talk about what you think is the actual horror. Amid all this death and devastation and utter despondency, he is talking about the living. Amid all this, Primo Levi is out observing people who survived this hell. Amid all this, Primo Levi is observing the results of a unique social experiment.

All excerpts below have been taken from the books If this is a man and the Truce

In our time many men have lived in this cruel manner, crushed against the bottom, but for a relatively short period; so that we can perhaps ask ourselves if it is necessary or good that any memory of this exceptional human state be retained.

To this question we feel that we have to reply in the affirmative. Indeed, we are convinced that no human experience is without meaning or unworthy of analysis, and that fundamental values, even if they are not always positive, can be deduced from this particular world which we are describing. We would like to consider how the Lager was also, and preeminently, a gigantic biological and social experiment.

Let thousands of individuals, differing in age, condition, origin, language, culture, and customs, be enclosed within barbed wire, and there be subjected to a regular, controlled life, which is identical for all and inadequate for all needs. No one could have set up a more rigorous experiment to determine what is inherent and what acquired in the behavior of the human animal faced with the struggle for life.

We do not believe in the most obvious and facile deduction: that man is fundamentally brutal, egoistic, and stupid in his conduct once every civilized institution is taken away, and that the “Häftling” is consequently nothing but a man without inhibitions. We believe, rather, that the only conclusion to be drawn is that, in the face of driving need and physical privation, many habits and social instincts are reduced to silence.

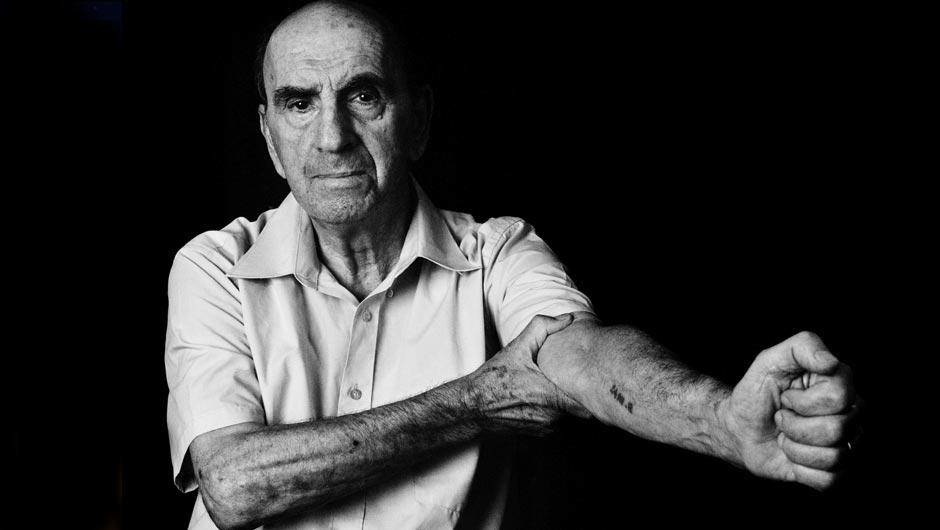

I am a Häftling. My name is 174517

Then for the first time we become aware that our language lacks words to express this offense, the demolition of a man. In a moment, with almost prophetic intuition, the reality has been revealed to us: we have reached the bottom. It’s not possible to sink lower than this; no human condition more wretched exists, nor could it be imagined. Nothing belongs to us anymore; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listened, they would not understand. They will take away even our name; and if we want to keep it, we will have to find in ourselves the strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, remains.

We know that we are unlikely to be understood, and that this is as it should be. But consider what value, what meaning is contained in even the smallest of our daily habits, in the hundred possessions of even the poorest beggar: a handkerchief, an old letter, the photograph of a cherished person. These things are part of us, almost like limbs of our body; it is inconceivable to be deprived of them in our world, for we would immediately find others to replace the old ones, other objects that are ours as guardians and evocations of our memories.

Imagine now a man who has been deprived of everyone he loves, and at the same time of his house, his habits, his clothes, of literally everything, in short, that he possesses: he will be a hollow man, reduced to suffering and needs, heedless of dignity and restraint, for he who loses everything can easily lose himself. He will be a man whose life or death can be lightly decided, with no sense of human affinity—in the most fortunate case, judged purely on the basis of utility. It is in this way that one can understand the double meaning of the term “extermination camp,” and it will be clear what we seek to express with the phrase “lying on the bottom.”

Häftling: I have learned that I am a Häftling. My name is 174517; we have been baptized, we will carry the mark tattooed on our left arm until we die.

The operation was slightly painful and extraordinarily rapid: they placed us all in a row, and, one by one, according to the alphabetical order of our names, we filed past a skilled official, armed with a sort of pointed tool with a very short needle. It seems that this is the true initiation: only by “showing one’s number” can one get bread and soup. It took several days, and not a few slaps and punches, for us to become used to showing our number promptly enough not to hold up the daily operation of food distribution; weeks and months were needed to learn its sound in the German language. And for many days, when the habits of freedom still led me to look for the time on my wristwatch, my new name, ironically, appeared instead, a number tattooed in bluish characters under the skin.

STEINLAUF

I must confess: after only a week of prison, the instinct for cleanliness disappeared in me. I wander aimlessly around the washhouse, and suddenly I see my friend Steinlauf, who is almost fifty, stripped to the waist, scrubbing his neck and shoulders with little success (he has no soap) but with great energy. Steinlauf sees me and greets me, and without preamble asks me severely why I do not wash. Why should I wash?

Would I be better off than I am? Would I be more pleasing to someone? Would I live a day, an hour longer? I would probably live a shorter time, because washing is work, a waste of energy and warmth. Doesn’t Steinlauf know that after half an hour with the coal sacks every difference between him and me will have disappeared? The more I think about it, the more washing one’s face in our condition seems a stupid chore, even frivolous: a mechanical habit, or, worse, a grim repetition of an extinct rite. We will all die, we are all about to die. If they give me ten minutes between reveille and work, I want to devote them to something else, to withdraw into myself, to take stock, or perhaps look at the sky and think that I may be looking at it for the last time; or even to let myself live, to indulge in the luxury of an idle moment.

But Steinlauf contradicts me. He has finished washing and is now drying himself with his cloth jacket, which he was holding rolled up between his knees and will soon put on. And without interrupting the operation he administers a full-scale lesson.

It grieves me now that I have forgotten his plain, clear words, the words of ex-Sergeant Steinlauf of the Austro-Hungarian Army, Iron Cross in the 1914–18 war. It grieves me because it means that I have to translate his uncertain Italian and his quiet speech, the speech of a good soldier, into my language of an incredulous man. But this was the sense, not forgotten then or later: that precisely because the Lager was a great machine to reduce us to beasts, we must not become beasts; that even in this place one can survive, and therefore one must want to survive, to tell the story, to bear witness; and that to survive we must force ourselves to save at least the skeleton, the scaffolding, the form of civilization. We are slaves, deprived of every right, exposed to every insult, condemned to almost certain death, but we still possess one power, and we must defend it with all our strength, for it is the last—the power to refuse our consent. So we must certainly wash our faces without soap in dirty water and dry ourselves on our jackets. We must polish our shoes, not because the rules prescribe it but for dignity and propriety. We must walk erect, without dragging our feet, not in homage to Prussian discipline but to remain alive, to not begin to die.

These things Steinlauf, a man of goodwill, told me: strange things to my unaccustomed ear, understood and accepted only in part, and softened by an easier, more flexible, and blander doctrine, which for centuries has drawn breath on the other side of the Alps, and according to which, among other things, there is no greater vanity than to force oneself to swallow whole moral systems elaborated by others, under another sky. No, the wisdom and virtue of Steinlauf, certainly good for him, is not enough for me. In the face of this complicated netherworld my ideas are confused; is it really necessary to elaborate a system and put it into practice? Or would it not be better to acknowledge that one has no system?

NULL ACHTZEHN

No, I honestly don’t feel that my companion of today, yoked with me under the same load, is either enemy or rival.

He is Null Achtzehn. He is not called anything but that, Zero Eighteen, the last three figures of his entry number: as if everyone were aware that only a man is worthy of a name, and that Null Achtzehn is no longer a man. I think that even he has forgotten his name—certainly he acts as if this were so. When he speaks, when he looks around, he gives the impression of being empty inside, no more than a husk, like the slough of some insect that one finds on the edge of a pond, attached to the rocks by a thread and shaken by the wind.

Null Achtzehn is very young, which is a grave danger. Not only because it’s harder for boys than for men to withstand fatigue and fasting but, even more, because long training in the struggle of each against all is needed to survive here, training that young people rarely have. Null Achtzehn is not even particularly weak, but all avoid working with him. He is indifferent to the point where he doesn’t trouble to avoid labor or blows or to search for food. He carries out every order he is given, and it’s predictable that when they send him to his death he will go with the same total indifference.

He doesn’t have even the rudimentary cunning of a draft horse, which stops pulling just before it reaches exhaustion; he pulls or carries or pushes as long as his strength allows, then gives way suddenly, without a word of warning, without lifting his sad, opaque eyes from the ground. He reminds me of the sled dogs in books by Jack London, who labor until their last breath and die on the track.

But, since the rest of us try by every possible means to avoid excess effort, Null Achtzehn is the one who works more than anybody. Because of this, and because he is a dangerous companion, no one wants to work with him; and since, on the other hand, no one wants to work with me, because I am weak and clumsy, it often happens that we find ourselves paired.

RESNYK

To have a bed companion of tall stature is a misfortune and means losing hours of sleep; I always get tall companions, because I am small and two tall men cannot sleep together. But it was immediately apparent that Resnyk, in spite of that, was not a bad companion. He spoke little and courteously, he was clean, he didn’t snore, didn’t get up more than two or three times a night and always with great delicacy. In the morning he offered to make the bed (this is a complicated and difficult operation, and also carries a notable responsibility, as those who make the bed badly, the schlechte Bettenbauer, are diligently punished) and did it quickly and well; so that I felt a certain fleeting pleasure later, in Roll Call Square, in seeing that he had been assigned to my Kommando.

On the march to work, limping in our clumsy wooden clogs on the icy snow, we exchanged a few words, and I found out that Resnyk is Polish; he lived in Paris for twenty years but still speaks an implausible French. He is thirty, but, like all of us, could be taken for anywhere from seventeen to fifty. He told me his story, and today I have forgotten it, but it was certainly a sorrowful, cruel, and moving story; because such are all our stories, hundreds of thousands of stories, all different and all full of a tragic, shocking necessity. We tell them to one another in the evening, and they take place in Norway, Italy, Algeria, Ukraine—simple and incomprehensible, like the stories in the Bible. But are not they, too, stories in a new Bible?

Once we arrived at the construction site, we were led to the Eisenröhreplatz, the flat area where the iron pipes are unloaded, and then the usual things began. The Kapo took the roll call again, briefly took note of the new acquisition, and arranged with the civilian Meister about the day’s work. He then entrusted us to the Vorarbeiter and went off to sleep in the toolshed, next to the stove; he is not a Kapo who makes trouble, for he is not a Jew and so has no fear of losing his post. The Vorarbeiter distributed the iron levers among us and the jacks among his friends. The usual little struggle took place to get the lightest levers, and today it went badly for me: mine is the twisted one that weighs perhaps fifteen kilograms; I know that even if I had to use it without any weight on it, I would be dead from exhaustion in half an hour.

Then we left, each with his own lever, limping in the melting snow. At every step, a little snow and mud stick to our wooden soles, until we’re walking unsteadily on two heavy, shapeless masses from which it’s impossible to get free; suddenly one comes unstuck, and then it’s as if one leg were several centimeters shorter than the other.

Today we have to unload an enormous cast-iron cylinder from the freight car. I think it is a synthesis pipe and must weigh several tons. This is better for us, because it is notoriously less exhausting to work with big loads than with small ones; in fact, the work is better subdivided, and we are given adequate tools. However, it is dangerous, one must not get distracted; a moment’s inattention and one would be crushed.

Meister Nogalla, the Polish foreman, rigid, serious, and taciturn, supervised in person the unloading operation. Now the cylinder lies on the ground and Meister Nogalla says, “Bohlen holen.”

Our hearts sink. It means “carry ties,” in order to build a path in the soft mud on which the cylinder will be pushed by the levers into the factory. But the ties are jammed in the ground and weigh eighty kilos; they are more or less at the limit of our strength. The more robust of us, working in pairs, are able to carry ties for a few hours; for me it is a torture; the load maims my shoulder bone. After the first trip, I am deaf and almost blind from the effort, and I would stoop to any baseness to avoid the second.

I will try and pair myself with Resnyk; he seems a good worker and, being taller, will support the greater part of the weight. I know it’s in the order of things for Resnyk to refuse me with contempt and team up with someone more robust; then I will ask to go to the latrine and I will remain there as long as possible, and afterward I will try to hide, with the certainty of being immediately tracked down, mocked, and hit; but anything is better than this work.

Instead Resnyk accepts, and, what’s more, lifts up the tie by himself and rests it on my right shoulder with care; then he lifts up the other end, places his left shoulder under it, and we set out.

The tie is encrusted with snow and mud; at every step it knocks against my ear and the snow slides down my neck. After fifty steps I am at the limit of what is usually called normal endurance: my knees are folding, my shoulder aches as if clasped in a vise, my balance is in danger. At every step I feel my shoes sucked in by the greedy mud, by this ubiquitous Polish mud whose monotonous horror fills our days.

I bite my lips deeply; we know well that gaining a small, extraneous pain serves as a stimulant to mobilize our last reserves of energy. The Kapos also know it: some of them beat us from pure bestiality and violence, but others beat us almost lovingly when we are carrying a load, accompanying the blows with exhortations and encouragement, as cart drivers do with willing horses.

When we reach the cylinder, we unload the tie on the ground, and I stand stiffly, my eyes vacant, mouth open, and arms dangling, sunk in the ephemeral and negative ecstasy of the cessation of pain. In a twilight of exhaustion I wait for the push that will force me to begin work again, and I try to take advantage of every second of waiting to recover some energy.

But the push never comes: Resnyk touches my elbow, we return as slowly as possible to the ties. There the others are wandering around in pairs, all trying to delay as long as possible before submitting to the load.

“Allons, petit, attrape.” This tie is dry and a little lighter, but at the end of the second journey I go to the Vorarbeiter and ask to go the latrine.

….

When I return to work, the trucks with the rations can be seen passing, which means it is ten o’clock. That is already a respectable hour, as the midday pause can be glimpsed in the fog of the remote future, and we can begin to derive some energy from the expectation.

I make two or three more trips with Resnyk, searching attentively, even going to distant piles, to find lighter ties, but by now all the best ones have been moved and only the others remain, repellent, sharp edged, heavy with mud and ice, and with metal plates nailed to them for the rails to fit on.

THE MARKET

The Market is always very active. Although every exchange (in fact, every form of possession) is explicitly forbidden, and although frequent sweeps by Kapos or Blockälteste periodically rout merchants, customers, and the curious, nevertheless the northeast corner of the camp (significantly, the corner farthest from the SS barracks) is permanently occupied by a tumultuous throng, in the open in summer, in a washhouse in winter, as soon as the squads return from work.

Here scores of prisoners, made desperate by hunger, prowl around, with lips parted and eyes gleaming, lured by a false instinct to where the merchandise displayed makes the gnawing in their stomachs more acute and their salivation more persistent. At best, they possess a miserable half-ration of bread that, with painful effort, they have saved since the morning, in the foolish hope of a chance to make an advantageous bargain with some ingenuous person who is unaware of the prices of the moment. Some, with savage patience, acquire a liter of soup with their half-ration, from which, having moved away from the crowd, they methodically extract the few pieces of potato lying at the bottom; this done, they exchange it for bread, and the bread for another liter to denature, and so on until their nerves are exhausted, or until some victim, catching them in the act, inflicts on them a severe lesson, exposing them to public derision. Those who come to the Market to sell their only shirt belong to the same species; they well know what will happen on the next occasion that the Kapo finds out that they are naked beneath their jacket. The Kapo will ask them what they have done with their shirt; it is a purely rhetorical question, a formality useful only for opening the exchange. They will reply that their shirt was stolen in the washhouse; this reply is equally standard, and is not expected to be believed; in fact, even the stones of the Lager know that ninety-nine times out of a hundred those who have no shirt have sold it out of hunger, and that in any case one is responsible for one’s shirt because it belongs to the Lager. So the Kapo will beat them, they’ll be issued another shirt, and sooner or later they’ll begin again.

The professional merchants are stationed in the Market, each in his usual corner; first among them are the Greeks, as immobile and silent as sphinxes, squatting on the ground behind bowls of thick soup, the fruits of their labor, their organizing, and their national solidarity. By now the Greeks have been reduced to very few, but they have made a contribution of major importance to the physiognomy of the camp and to the international slang in circulation. Everyone knows that caravana is the bowl, and that “la comedera es buena” means that the soup is good; the word that expresses the generic idea of theft is klepsi-klepsi, of obvious Greek origin. These few survivors from the Jewish colony of Salonika, with their two languages, Spanish and Greek, and their numerous activities, are the repositories of a concrete, worldly, conscious wisdom, in which the traditions of all the Mediterranean civilizations converge. In the camp this wisdom has been transformed into the systematic and scientific practice of theft and seizure of posts of authority, and into a monopoly on the barter Market. But this should not let us forget that their aversion to gratuitous brutality, their amazing consciousness of the survival of at least the potential of human dignity, made the Greeks the most coherent national group in the Lager and, in this respect, the most civilized.

At the Market you can find specialists in kitchen thefts, their jackets swelled by mysterious bulges. Whereas there is a virtually stable price for soup (half a ration of bread for a liter), the price of turnips, carrots, potatoes is extremely variable and depends greatly on, among other factors, the diligence and the corruptibility of the guards on duty at the warehouses.

Mahorca is sold. Mahorca is a third-rate tobacco, in the form of woody chips, which is officially on sale at the Kantine in fifty-gram packets, in exchange for “prize coupons” that Buna is supposed to distribute to the best workers. That distribution occurs irregularly, with great parsimony and manifest unfairness, so that the majority of coupons end up, either directly or through the abuse of authority, in the hands of the Kapos and the Prominents; nevertheless, the prize coupons still circulate on the market in the form of money, and their value changes in strict obedience to the laws of classical economics.

There have been periods in which the prize coupon was worth one ration of bread, then one and a quarter, even one and a third; one day it was quoted at one and a half rations, but then the supply of Mahorca failed to arrive at the Kantine, so that, lacking coverage, the currency dropped abruptly to a quarter of a ration. Another boom period occurred for a singular reason: the changing of the guard at the Frauenblock, with the arrival of a fresh contingent of robust Polish girls. In fact, since the prize coupon is valid for entry into the Frauenblock (for the criminals and the politicals; not for the Jews, who, on the other hand, are not affected by this restriction), interested parties cornered the market actively and rapidly: hence the revaluation, which, however, did not last long.

Among the ordinary Häftlinge there are not many who search for Mahorca to smoke it personally; for the most part, it leaves the camp and ends up in the hands of the civilian workers in Buna. This is a very widespread system of kombinacja: the Häftling, somehow saving a ration of bread, invests it in Mahorca; he cautiously gets in touch with a civilian addict, who buys the Mahorca, paying as it were in cash, with a portion of bread greater than that initially invested. The Häftling eats the surplus, and puts the remaining ration back on the market. Speculations of this kind establish a tie between the internal economy of the Lager and the economic life of the outside world: when the distribution of tobacco to the civilian population of Kraków accidentally failed, that fact, crossing the barbed-wire barrier that segregates us from human society, had an immediate repercussion in the camp, provoking a notable rise in the price of Mahorca and, consequently, of the prize coupon.

The process outlined above is only the simplest type; a more complex one is the following. The Häftling acquires in exchange for Mahorca or bread, or maybe receives as a gift from a civilian, some abominable, torn, dirty rag of a shirt, which must, however, have three holes suitable for the head and arms to more or less fit through. As long as it shows signs only of wear, and not of artificial mutilations, such an object, at the moment of the Wäschetauschen, is valid as a shirt and carries the right to an exchange; at most, the person who presents it will receive an appropriate number of blows for having taken so little care of the regulation clothing.

Consequently, within the Lager, there is no great difference in value between a shirt worthy of the name and a rag covered with patches. The Häftling described above will have no difficulty in finding a comrade in possession of a shirt of commercial value who is unable to capitalize on it, as he is not in touch with civilian workers, because of his place of work, or because of language, or because of intrinsic incapacity; this latter will be satisfied with a modest amount of bread for the exchange, and in fact the next Wäschetauschen will to a certain extent reestablish equilibrium, distributing good and bad clothes in a perfectly random manner. But the first Häftling will be able to smuggle the good shirt into Buna and sell it to the original (or any other) civilian for four, six, even ten rations of bread. This high margin of profit reflects the gravity of the risk of leaving camp wearing more than one shirt or reentering with none.

There are many variations on this theme. Some do not hesitate to have the gold crowns on their teeth extracted so as to sell them in Buna for bread or tobacco. But it is more usual for such traffic to take place through an intermediary. A high number, that is, a new arrival, only recently but sufficiently brutalized by hunger and by the extreme tension of life in the camp, is noticed by a low number for the abundance of his gold teeth; the low offers the high three or four rations of bread, to be paid in return for extraction. If the high number accepts, the low one pays, and takes the gold to Buna, where, if he is in contact with a trustworthy civilian, who he is not afraid will inform on or cheat him, he can make a sure gain of between ten and twenty or even more rations, which are paid to him gradually, one or two a day. It is worth noting in this respect that, contrary to what takes place in Buna, the maximum amount of any transaction negotiated within the camp is four rations of bread, because it would be practically impossible either to enter into contracts on credit or to safeguard a larger quantity of bread from the greed of others or from one’s own hunger.

Trafficking with civilians is a characteristic element of the Arbeitslager and, as we have seen, determines its economic life. On the other hand, it is a crime, explicitly provided for in the camp regulations, and considered equivalent to a “political” crime; hence it is punished with particular severity. The Häftling convicted of Handel mit Zivilisten, unless he can rely on influential protection, ends up at Gleiwitz III, Janina, or Heidebreck, in the coal mines, which means death from exhaustion within a few weeks. Moreover, his accomplice, the civilian worker, may also be reported to the appropriate German authority and condemned to spend in the Vernichtungslager, under the same conditions as us, a period varying, as far as I know, from a fortnight to eight months. The workers on whom this retribution is imposed are stripped on entry, like us, but their personal possessions are kept in a special storeroom. They are not tattooed, and they keep their hair, which makes them easily recognizable, but for the entire duration of their punishment they are subjected to the same work and the same discipline as us—except, of course, the selections.

They work in separate Kommandos and have no contact of any sort with the common Häftlinge. In fact, for them the Lager is a punishment, and if they do not die of exhaustion or illness they can expect to return among men; if they could communicate with us, it would constitute a breach in the wall that makes us dead to the world, and a glimpse into the mystery that prevails among free men about our condition. For us, on the contrary, the Lager is not a punishment; for us, no end is foreseen and the Lager is nothing but the kind of existence that has been allotted to us, without time limits, within the German social organism.

One section of our camp is in fact set aside for civilian workers, of all nationalities, who are compelled to stay there for a longer or shorter period in expiation of their illicit relations with Häftlinge. This section is separated from the rest of the camp by barbed wire, and is called E-Lager, and its guests E-Häftlinge. “E” is the initial for Erziehung, which means “education.”

All the transactions outlined above are based on the smuggling of materials belonging to the Lager. This is why the SS are so rigorous in suppressing them: the very gold of our teeth is their property, as, sooner or later, torn from the mouths of the living or the dead, it ends up in their hands. So it is natural that they should do their best to see that the gold does not leave the camp.

But against theft in itself the camp authorities have no prejudice. The attitude of open connivance by the SS in regard to smuggling in the opposite direction shows this clearly.

Here things are generally simpler. It is a question of stealing or receiving any of the various tools, utensils, materials, products, etc., with which we come in daily contact in Buna in the course of our work, of introducing them into the camp in the evening, of finding a customer, and of carrying out the exchange for bread or soup. This traffic is intense: in regard to certain articles, although they are necessary for the normal life of the camp, this method of theft in Buna is the only and regular means of procurement. Typical are the cases of brooms, paint, electrical wire, grease for shoes. The trade in this last item will serve as an example.

As we have already noted, the camp regulations prescribe that shoes must be greased and polished every morning, and every Blockältester is responsible to the SS for compliance with this order by all the men in his barrack. One might think, then, that each barrack would enjoy a periodic assignment of grease for shoes, but this is not so; the mechanism is completely different. It should be stated first that each barrack receives an evening allotment of soup somewhat higher than that prescribed for regulation rations; this extra amount is divided according to the discretion of the Blockältester, who first of all distributes it as a gift to his friends and protégés, then as recompense to the sweepers, the night guards, the lice inspectors, and all the other Prominents and functionaries. What is still left (and every smart Blockältester makes sure that there is always some) is used precisely for these purchases.

The rest is obvious. Those Häftlinge who in Buna have the chance to fill their bowl with grease or machine oil (or anything else: any blackish and greasy substance is considered suitable for the purpose) on their return to the camp in the evening make a systematic tour of the barracks until they find a Blockältester who lacks the article or wants to stock up. In fact, each barrack usually has its habitual supplier, with whom a fixed daily payment has been agreed on, on condition that he provide the grease whenever the supply is about to run out.

Every evening, next to the doors of the Tagesräume, the groups of suppliers stand around patiently; on their feet for hours and hours in the rain or snow, they discuss excitedly, in low tones, matters relating to the fluctuation of prices and the value of the prize coupon. Every now and again one of them leaves the group, makes a quick visit to the Market, and returns with the latest news.

Besides the articles already described, there are innumerable others to be found in Buna, which might be useful to the Block or welcomed by the Blockältester, or might excite the interest or curiosity of the Prominents: lightbulbs, brushes, ordinary or shaving soap, files, pliers, sacks, nails. Methyl alcohol is sold to make drinks, and gas is useful for rudimentary lighters, marvels of the secret industry of Lager craftsmen.

In this complex network of thefts and counter-thefts, fueled by the silent hostility between the SS command and the civilian authorities of Buna, Ka-Be plays a role of prime importance. Ka-Be is the place of least resistance, where the regulations can most easily be avoided and the surveillance of the Kapos eluded. Everyone knows that it is the nurses themselves who send back to the Market, at low prices, the clothes and shoes of the dead and of the selected, who leave naked for Birkenau; it is the nurses and doctors who export the allotment of sulfonamides to Buna, selling them to civilians for foodstuffs.

The nurses also make a huge profit from the trade in spoons. The Lager does not provide new arrivals with spoons, although the semiliquid soup cannot be consumed without one. The spoons are manufactured in Buna, secretly and in spare moments, by Häftlinge who work as specialists in the Kommandos of iron and tin workers. These spoons are crude and clumsy tools, hammered out of aluminum, and often have a sharp handle that also serves as a knife for cutting bread. The manufacturers themselves sell these directly to the new arrivals: an ordinary spoon is worth half a ration of bread, a knife-spoon three-quarters of a ration. Now, it is a law that although one can enter Ka-Be with one’s spoon, one cannot leave with it. As those who get better are about to be released, and before they are given clothes, their spoon is confiscated by the nurses and put up for sale in the Market. Adding the spoons of the patients about to leave to those of the dead and the selected, the nurses receive profits from the sale of about fifty spoons every day. On the other hand, the discharged patients are forced to begin work again with the initial disadvantage of half a ration of bread, allocated for the purchase of a new spoon.

Finally, Ka-Be is the main customer and receiver of goods stolen in Buna: of the soup assigned to Ka-Be, a good twenty liters are set aside each day as the theft fund to acquire the most varied goods from the specialists. Some steal thin rubber tubing, which is used in Ka-Be for enemas and stomach pumps; others offer colored pencils and inks, necessary for Ka-Be’s complicated bookkeeping system; and thermometers, and laboratory glassware, and chemicals, which vanish from the Buna stores in the Häftlinge’s pockets and find a use in the infirmary as medical equipment.

And I would not be guilty of immodesty if I add that it was our idea, mine and Alberto’s, to steal rolls of graph paper from the thermographs of the Drying Department, and offer them to the Medical Chief of Ka-Be with the suggestion that they be used as forms for pulse-temperature charts.

In conclusion: theft in Buna, punished by the civilian authorities, is sanctioned and encouraged by the SS; theft in the camp, severely repressed by the SS, is considered by the civilians a normal operation of exchange; theft among Häftlinge is generally punished, but the punishment strikes the thief and the victim with equal severity. We now invite the reader to contemplate the possible meaning in the Lager of the words “good” and “evil,” “just” and “unjust”; let each judge, on the basis of the picture outlined and the examples given above, how much of our ordinary moral world could survive on this side of the barbed wire.

THE FIRST RUSSIANS

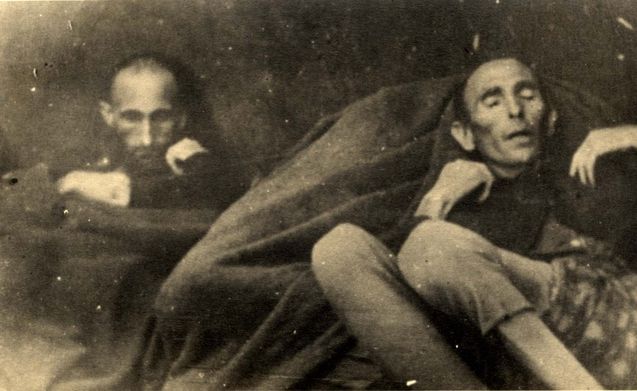

The first Russian patrol came in view of the camp around midday on January 27, 1945.

Four young soldiers on horseback, machine guns under their arms, proceeded warily along the road that followed the perimeter of the camp. When they reached the fences, they paused to look, and, with a brief, timid exchange of words, turned their gazes, checked by a strange embarrassment, to the jumbled pile of corpses, to the ruined barracks, and to us few living beings.

They seemed to us miraculously physical and real, suspended (the road was higher than the camp) on their enormous horses, between the gray of the snow and the gray of the sky, motionless under the gusts of a damp wind that threatened thaw.

It seemed to us, and so it was, that the void filled with death in which for ten days we had wandered like spent stars had found a solid center, a nucleus of condensation: four armed men, but not armed against us; four messengers of peace, with rough boyish faces under the heavy fur helmets.

They didn’t greet us, they didn’t smile; they appeared oppressed, not only by pity but by a confused restraint, which sealed their mouths, and riveted their eyes to the mournful scene. It was a shame well-known to us, the shame that inundated us after the selections and every time we had to witness or submit to an outrage: the shame that the Germans didn’t know, and which the just man feels before a sin committed by another. It troubles him that it exists, that it has been irrevocably introduced into the world of things that exist, and that his goodwill availed nothing, or little, and was powerless to defend against it.

So for us even the hour of freedom struck solemn and oppressive, and filled our hearts with both joy and a painful sense of shame, because of which we would have liked to wash from our consciences and our memories the monstrosity that lay there; and with anguish, because we felt that this could not happen, that nothing could ever happen that was good and pure enough to wipe out our past, and that the marks of the offense would remain in us forever, and in the memories of those who were present, and in the places where it happened, and in the stories that we would make of it. Since—and this is the tremendous privilege of our generation and of my people—no one could ever grasp better than us the incurable nature of the offense, which spreads like an infection. It is foolish to think that it can be abolished by human justice. It is an inexhaustible source of evil: it breaks the body and soul of those who are drowned, extinguishes them and makes them abject; rises again as infamy in the oppressors, is perpetuated as hatred in the survivors, and springs up in a thousand ways, against the very will of all, as a thirst for revenge, as moral breakdown, as negation, as weariness, as resignation.

These things, at the time not clearly discerned, and noted by the majority only as a sudden wave of mortal fatigue, accompanied the joy of liberation. Therefore few among us ran to the saviours, few fell in prayer. Charles and I stood still near the ditch overflowing with livid limbs, while others knocked down the fence; then we returned with the empty stretcher, to bring the news to our companions.

For the rest of the day nothing happened, a thing that did not surprise us, and that we had long since become accustomed to.

THE GREEK

Toward the end of February, after a month in bed, I felt not recovered but stable. I had the clear impression that, until I got myself (maybe with an effort) into a vertical position, and put shoes on my feet, I wouldn’t regain health and strength. So on one of the rare examination days, I asked to be discharged.

I was hoping for a few days of rest and gradual practice for an active life, but I didn’t know I had been unlucky. Immediately, the next morning, I fell into a Russian transport heading for a mysterious transit camp.

I can’t recall exactly how and when my Greek emerged out of the nothingness. In those days and in those places, shortly after the front passed, a high wind blew over the face of the Earth: the world around us seemed to have returned to a primal Chaos, and was swarming with deformed, defective, abnormal human examples; and each of them was tossing about, in blind or deliberate motion, anxiously searching for his own place, his own sphere, as the cosmogonies of the ancients say, poetically, of the particles of the four elements.

I, too, overwhelmed by the whirlwind, thus found myself many hours before dawn on a freezing night, after a copious snowfall, loaded onto a horse-drawn military cart, along with a dozen companions I didn’t know. The cold was intense; the sky, thick with stars, was growing light in the east, promising one of those marvelous sunrises of the plain that, in the time of our slavery, we watched interminably from Roll Call Square in the Lager.

Our guide and escort was a Russian soldier.

His name was Mordo Nahum, and at first sight he appeared unremarkable, except for his shoes (leather, almost new, of an elegant model: a true miracle, given the time and the place), and the sack that he carried on his back, which had a considerable mass and a corresponding weight, as I was to verify in the days that followed. In addition to his own language, he spoke Spanish (like all the Jews of Salonika), French, a broken Italian but with a good accent, and, I found out later, Turkish, Bulgarian, and a little Albanian. He was forty; he was quite tall, but he walked bent over, with his head forward, as if he were nearsighted. He was red-haired and red-skinned, he had large pale, watery eyes, and a big hooked nose, which gave his entire person an aspect at once rapacious and clumsy, as of a nocturnal bird surprised by the light, or a predator fish out of its natural element.

He was recovering from an unspecified illness, which had caused spells of a very high, debilitating fever; even then, on the first nights of the journey, he sometimes fell into a state of prostration, shivering and delirious. Yet, without feeling particularly attracted to each other, we were brought together by two common languages, and by the fact—very noticeable in the circumstances—that we were the only two Mediterraneans in the little group.

We had hoped for a short and safe journey, toward a camp equipped to welcome us, toward an acceptable surrogate for our homes; and that hope was part of a much larger hope, hope in a right and just world, miraculously reestablished on its natural foundations after an eternity of disruptions, mistakes, and slaughters, after our long time of endurance. It was a naïve hope, like all hopes that rest on sharp divisions between evil and good, between past and future: but we lived on them. That first crack, and the many others, large and small, that inevitably followed, was a cause of suffering for many of us, the more deeply felt because it had not been foreseen: since one does not dream for years, for decades, of a better world without imagining it to be perfect.

Instead no, something had happened that only a very few sages among us had predicted. Freedom, improbable, impossible freedom, so far from Auschwitz that only in dreams had we dared to hope for it, had arrived: but it had not brought us to the Promised Land. It was around us, but in the form of a pitiless, deserted plain. More trials awaited us, more labors, more hunger, more cold, more fears.

I had now been without food for twenty-four hours. We sat on the wooden floor of the train car, close against one another to protect ourselves from the cold; the tracks were uneven, and at every jolt our heads, infirm on our necks, bumped against the wooden sides. I felt exhausted, not only in my body: like an athlete who has run for hours, using up all his resources, the natural ones first, and then the ones that are squeezed out, created from nothing in moments of extreme need; an athlete who arrives at the finish line, and, in the act of collapsing, exhausted, on the ground, is brutally pulled to his feet and forced to start running again, in the dark, toward another finish line, an unknown distance away. I had bitter thoughts: that nature rarely grants compensation, and neither does human society, being timid and slow to diverge from nature’s gross schemes; and such an achievement would represent, in the history of human thought, the ability to see in nature not a model to follow but a shapeless block to carve, or an enemy to fight.

The train traveled slowly. In the evening, dark, apparently deserted villages appeared; then utter night descended, atrociously frigid, with no lights in the sky or on the earth. Only the jolting of the car kept us from slipping into a sleep that the cold would have rendered fatal. Finally, after interminable hours of traveling, perhaps around three in the morning, we stopped in a small, dark, badly damaged station.

……

It had been a terrible night for everyone, perhaps the worst of our entire exile. I talked about it with the Greek: we found ourselves in agreement in deciding to form an alliance with the purpose of avoiding by any means another freezing night, which we felt we wouldn’t survive.

I think that the Greek, thanks to my nighttime expedition, in some way overestimated my qualities as a débrouillard et démerdard (resourceful and nerdy), as people used, elegantly, to say. As for me, I confess that I counted chiefly on his large sack, and the fact that he was a Salonikan, which, as everyone at Auschwitz knew, was a guarantee of sophisticated mercantile skills, of knowing how to get by in all circumstances. Liking, on both sides, and respect, on one, came later.

We departed again in the afternoon. The sun shone. Our wretched train stopped at sunset, with engine trouble; in the distance the belltowers of Kraków glowed red. The Greek and I got out of the car, and went to question the engineer, who was standing in the snow, completely dirty, busily contending with jets of steam bursting from some broken pipe. “Maschina kaput,” he answered concisely. We were no longer slaves, we were no longer protected, we had emerged from guardianship. For us the hour of trial had come.

The Greek, restored by the hot soup of Szczakowa, felt in fairly good health. “On y va?” “On y va.” So we left the train and our bewildered companions, whom we would never have to see again, and set off on foot in a dubious search for the Civilized World.

Following his peremptory request, I was carrying the famous load. “But it’s your stuff!” I had tried in vain to protest. “Precisely because it’s mine. I organized it and you carry it. It’s the division of labor. Later, you’ll profit from it, too.” So we walked, he first and I second, on the trampled snow of a street on the outskirts; the sun had set.

I’ve already mentioned the Greek’s shoes; as for me, I wore a pair of odd shoes such as in Italy I’ve seen worn only by priests: of very delicate leather, up to the anklebone, with two large pins and no laces, and two side pieces of an elastic material that were supposed to ensure that they closed and stayed on. I also wore a good four pairs of pants of Häftling material, a cotton shirt, a jacket that was also striped, and that’s all. My baggage consisted of a blanket and a cardboard box in which I had first saved some pieces of bread but which was now empty—all things that the Greek looked at with unconcealed contempt and scorn.

We had been grossly deceived about the distance to Kraków: we would have to go at least seven kilometers. After twenty minutes of walking, my shoes were gone; the sole of one had fallen off, and the other was coming undone. The Greek had until then preserved a meaningful silence. When he saw me put down the bundle, and sit on a stone marker to observe the disaster, he asked me: “How old are you?”

“Twenty-five,” I answered.

“What is your profession?”

“I’m a chemist.”

“Then you’re a fool,” he said calmly. “Anyone who doesn’t have shoes is a fool.”

He was a fine Greek. Few times in my life, before or since, have I felt such concrete wisdom hanging over my head. I could hardly object. The validity of the argument was palpable, obvious: the two formless wrecks on my feet, and the two shining marvels on his. There was no excuse. I was no longer a slave, but, after the first steps on the path of freedom, here I was sitting on a post, with my feet in my hand, clumsy and useless as the broken-down locomotive we had just left. So did I deserve freedom? The Greek seemed dubious.

“. . . But I had scarlet fever, I was in the infirmary: the shoe warehouse was far away, we weren’t allowed to get near it, and then they said it had been ransacked by the Poles. And didn’t I have the right to think that the Russians would provide them?”

“Words,” said the Greek. “Everybody knows how to say words. I had a forty degree fever, and I didn’t know if it was day or night. But one thing I knew, that I needed shoes and other things, so I got up and went to the warehouse to study the situation. And there was a Russian with a machine gun in front of the door; but I wanted shoes, and I walked around it, I broke a window, and I went in. So I had shoes, and also the sack and everything that’s in the sack, which will be useful later. That is foresight; yours is stupidity, it’s not taking account of the reality of things.”

“You’re the one who’s full of words now,” I said. “I may have made a mistake, but now we have to get to Kraków before night, with shoes or without.” And so saying I struggled, with my numb fingers, and with some bits of wire I had found on the road, to at least temporarily tie the soles to the uppers.

“Forget it, you’ll get nowhere like that.” He handed me two pieces of strong cloth he had dug out of his bundle, and showed me how to wrap up shoes and feet, so as to be able to walk as well as possible. Then we continued in silence.

The outskirts of Kraków were anonymous and bleak. The streets were utterly deserted; the shop windows were empty, all the doors and windows were barred or smashed. We reached the end of a tram line. I hesitated, since we had no way to pay for a ride, but the Greek said, “Get on, then we’ll see.” The car was empty; after a quarter of an hour the driver appeared, and not the conductor (from which you see that once again the Greek was right; and, as will be seen, he was right in all the affairs that followed, except one); we left, and during the journey we found with joy that one of the passengers who got on was a French soldier. He explained to us that he was billeted in an ancient convent, which the tram would soon pass; at the next stop, we would find a barrack requisitioned by the Russians and full of Italian soldiers. My heart rejoiced: I had found a home.

In reality everything did not go so smoothly. The Polish sentinel on guard at the barrack first invited us curtly to go away. “Where?” “What do I care? Away from here, anywhere.” After much persistence and prayer, he was finally induced to call an Italian marshal, evidently the one who made decisions on admitting other guests. It wasn’t simple, he explained to us: the barrack was already full to overflowing, the rations were limited; that I was Italian he could admit, but I wasn’t a soldier; as for my companion, he was Greek, and it was impossible to have him come in among former combatants in Greece and Albania—certainly scuffles and brawls would break out. I responded with my greatest eloquence, and with genuine tears in my eyes: I guaranteed that we would stay only one night (and thought to myself: once inside . . .), and that the Greek spoke Italian well and anyway would scarcely say a word. My arguments were weak and I knew it; but the Greek knew how all the military services of the world function, and while I was talking he was digging in the sack hanging on my shoulders. Suddenly he

pushed me aside and silently placed under the nose of the Cerberus a dazzling can of pork, adorned with a multicolored label, and with futile instructions in six languages on the right way to handle the contents. So we won a roof and a bed in Kraków.

It was now night. Contrary to what the marshal wished us to believe, inside the barrack the most sumptuous abundance reigned: there were lighted stoves, candles and carbide lamps, food and drink, and straw to sleep on. The Italians were arranged ten or twelve to a room, but we at Monowitz had been two per cubic meter. They wore good military clothes, padded jackets, many had wristwatches, all had hair shiny with brilliantine; they were noisy, cheerful, and kind, and overwhelmed us with attentions. As for the Greek, he was practically carried triumphantly. A Greek! A Greek is here! The news spread from room to room, and soon a festive crowd had gathered around my stern ally. They spoke Greek, some fluently, these veterans of the most pitiful military occupation that history records: they recalled with vivid sympathy places and events, in tacit, gallant recognition of the desperate valor of the invaded country. But there was something more, which opened the way for them: mine was not an ordinary Greek, he was visibly a master, an authority, a super Greek. In a few minutes of conversation, he had performed a miracle, had created an atmosphere.

He possessed the right equipment: he could speak Italian, and (what was more important, and is lacking in many Italians themselves) he knew what to talk about in Italian. He astonished me: he proved to be an expert in girls and spaghetti, in Juventus and opera, war and gonorrhea, wine and the black market, motorcycles and dodges. Mordo Nahum, with me so laconic, quickly became the center of the evening. I saw that his eloquence, his successful effort at captatio benevolentiae were not motivated only by opportunistic considerations. He, too, had fought in the Greek campaign, with the rank of sergeant: on the other side, of course, but this detail at this moment seemed negligible to everyone. He had been at Tepelenë, as had many Italians, too; he had, like them, suffered cold, hunger, mud, and bombardments; and at the end he, like them, had been captured by the Germans. He was a colleague, a fellow soldier.

He told curious war stories. Once, after the Germans broke through the front, he, along with six of his soldiers, had been ransacking the second floor of a bombed, abandoned villa in search of provisions, and had heard suspicious noises on the floor below; he had cautiously gone down the stairs with the machine gun on his hip, and had run into an Italian sergeant who with six soldiers was doing the same job on the ground floor. The Italian had leveled his gun, in turn, but the Greek had pointed out that in those conditions a gun battle would be especially stupid, that they were both, Greeks and Italians, in the same soup, and that he didn’t see why they couldn’t make a small separate local peace and continue searching in their respective occupied territories—a proposal that the Italian had readily agreed to.

For me, too, it was a revelation. I knew he was nothing but a somewhat shady merchant, expert in scams and without scruples, egotistical and cold, and yet I felt that, encouraged by the sympathy of his listeners, a new warmth flowered in him, an unsuspected humanity, singular but genuine, and rich in promise.

Late at night, from somewhere or other, a flask of wine appeared. It was the final blow: for me everything was celestially shipwrecked in a warm purple haze, and I barely managed to crawl on all fours to the bed of straw that the Italians, with maternal care, had made in a corner for the Greek and me.

Day had barely broken when the Greek woke me. Alas, disappointment! Where had the jovial guest of the night before gone? The Greek who was before me was hard, secretive, taciturn. “Get up,” he said in a tone that admitted no response. “Put on your shoes, get the sack, and let’s go.”

“Go where?”

“To work. To the market. Do you think it’s right to let someone support us?”

To this argument I felt completely resistant. It seemed to me that, apart from being comfortable, it was extremely natural for someone to support me, and also right. I had found the previous night’s explosion of national solidarity—rather, of spontaneous humanity—wonderful, thrilling. Besides, full of self-pity as I was, it seemed to me just, and good, that the world should finally feel compassion for me. In any case, I didn’t have shoes, I was sick, I was cold, I was tired; and finally, in the name of heaven, what in the world could I do at the market?

I set out these considerations, which to me were obvious. But “C’est pas des raisons d’homme,” he answered, in irritation: I had to realize that I had insulted an important moral principle of his, that he was seriously shocked, that on that point he was not disposed to negotiate or discuss. Moral codes, all of them, are rigid by definition: they do not admit nuances, or compromises, or mutual contamination. They are accepted or rejected entire. This is one of the main reasons that man is a herd animal, and more or less consciously seeks proximity not to his neighbor in general but only to one who shares his deep convictions (or his lack of such convictions). I had to realize, with disappointment and amazement, that such precisely was Mordo Nahum: a man of profound convictions, which, moreover, were very far from mine. Now, we all know how difficult it is to have business relations—indeed, to live together—with an ideological opposite.

Fundamental to his ethic was work, which he felt as a sacred duty but which he understood in a very broad sense. Work was that and only that which leads to gain without limiting freedom. The concept of work thus also includes, for example, besides certain legal activities, smuggling, theft, fraud (not robbery: he wasn’t a violent man). On the other hand, he considered reprehensible, because humiliating, all activities that do not involve initiative or risk, or that assume discipline and hierarchy: that is, any employee relationship, any providing of services, which, even if it was well compensated, he considered altogether “servile work.” But it wasn’t servile work to plow one’s own field, or sell fake antiquities to tourists at the port.

As for the loftier activities of the spirit, creative work, I quickly understood that the Greek was divided. These were a matter of delicate judgments, to be made case by case: it was permissible, for example, to pursue success in itself, even by selling fake paintings or bad literature, or anyway by harming one’s neighbor, but it was reprehensible to persist in following an unprofitable ideal, and sinful to withdraw from the world in contemplation. Permissible, however, in fact commendable, was the path of the man who devotes himself to meditation and acquiring wisdom, provided he doesn’t believe that he should receive his bread for nothing from the civilized world: even wisdom is goods, and can and should be exchanged.

Since Mordo Nahum was not a fool, he understood clearly that his principles could not be shared by individuals of different origin and upbringing, and in particular by me; but he was firmly convinced of them, and it was his ambition to translate them into acts, to show me their general validity.

In conclusion, my proposal to sit calmly and wait for bread from the Russians could only appear to him detestable: because it was “bread not earned”; because it involved a relationship of subjugation; and because every kind of order, of structure, was for him suspect, whether it led to a loaf every day or a pay envelope every month.

So I followed the Greek to the market, not so much because I was convinced by his arguments as through inertia and curiosity. The evening before, while I was navigating in a sea of vinous fogs, he had diligently informed himself of the location, customs, tariffs, demands, and supplies of the free market of Kraków, and duty called him.

We left, he with the sack (which I carried), I in my decrepit shoes, by virtue of which every single step became a problem. The market of Kraków had grown up spontaneously, right after the front passed by, and in a few days had occupied an entire neighborhood. You could buy or sell anything, and the whole city made its way there: bourgeois residents sold furniture, books, paintings, clothes, and silver; peasants padded like mattresses offered meat, chickens, eggs, cheese; children, their noses and cheeks reddened by the frigid wind, sought smokers for the rations of tobacco that the Soviet military administration distributed with peculiar generosity (three hundred grams a month for everyone, even newborns).

I was overjoyed to meet a small group of fellow countrymen: skilled types, three soldiers and a girl, cheerful and openhanded, who in those days were doing excellent business with hot pancakes, made with strange ingredients in a doorway not far away.

After a first general survey, the Greek decided on shirts. Were we partners? Well, he would contribute capital and mercantile experience; I, physical work and my (tenuous) knowledge of German. “Go,” he said, “and take a look at all the stalls where shirts are sold, ask how much they cost, say it’s too much, then come back and report. Don’t attract too much attention.” I prepared unwillingly to carry out this market research: I harbored in myself old hunger and cold, and inertia, and at the same time curiosity, carelessness, and a new, piquant desire to start conversations, to open human relations, to flaunt and waste my boundless freedom. But the Greek, behind the backs of my interlocutors, followed me with a harsh eye: hurry up, damn it, time is money, business is business.

I came back from my tour with some prices for reference, which the Greek made a mental note of, and with a certain number of disjointed philological notions: that “shirt” is said something like kosciúla; that Polish numerals resemble Greek ones; that “how much is it” and “what time is it” are said approximately ile kostúie and ktura gogína; a genitive ending in –ego that made clear to me certain Polish curses often heard in the Lager; and other shreds of information that filled me with a silly, childish joy.

…………

The soup kitchen was behind the cathedral: it remained to find out which, among the many beautiful churches of Kraków, was the cathedral. Whom to ask, and how? A priest went by: I would ask the priest. Now, that priest, young and with a kind face, understood neither French nor German; as a result, for the first and only time in my post-scholastic career, I got some use out of years of classical studies by initiating in Latin the strangest and most tangled of conversations. From the first request for information (“Pater optime, ubi est mensa pauperorum?”) we talked confusedly about everything, about my being a Jew, about the Lager (“castra”? “Lager” was better, unfortunately understood by anyone), about Italy, about the inadvisability of speaking German in public (which I came to understand later, through direct experience), and about countless other things, to which the unusual guise of the language gave a curious flavor of the pluperfect.

I had completely forgotten hunger and cold, since the need for human contact should truly be numbered among the elemental needs. I had even forgotten the Greek; but he hadn’t forgotten me, and showed up brutally after a few minutes, ruthlessly interrupting the conversation. Not that he was against human contact, and not that he didn’t understand the good of it (he had shown it the night before in the barrack): but these were things outside of working hours, for holidays, accessories, not to be mixed with that serious and strenuous business that is daily work. He responded to my weak protests only with a harsh look. We set off; the Greek was silent for a long time, then, in conclusive judgment of my assistance, he said to me thoughtfully, “Je n’ai pas encore compris si tu es idiot ou fainéant.”

Guided by the priest’s valuable information, we reached the soup kitchen, which was a very depressing place, but warm and full of delicious smells. The Greek ordered two soups and a single portion of beans with lard: it was the punishment for the unsuitable and foolish way I had behaved that morning. He was angry; but once he had swallowed the soup he softened noticeably, so much that he left me a good quarter of his beans. Outside it had begun to snow, and a savage wind was blowing. Maybe it was pity for my striped garments, or indifference toward the rules; for a large part of the afternoon, the kitchen staff left us alone, thinking, and making plans for the future. The Greek’s mood seemed to have changed: maybe the fever had returned, or maybe, after the solid business of the morning, he felt on vacation. He felt, in fact, in a benevolently pedagogical mood. Gradually, as the hours passed, the tone of his conversation imperceptibly warmed, and at the same time the relationship that bound us was changing: from master–slave at noon, to boss–employee at one, to master-disciple at two, to older brother–younger brother at three. The conversation returned to my shoes, which neither of us, for different reasons, could forget. He explained to me that to be without shoes is a very grave offense. In war, there are two things you must think of above all: in the first place shoes, in the second food, and not the other way around, as the populace maintains—because someone who has shoes can go around looking for food, while the opposite is not true. “But the war is over,” I objected; and I thought it was over, like many in those months of truce, in a more universal sense than one dares to think today. “There is always war,” Mordo Nahum answered, memorably.

We all know that no one is born with a set of rules, that each of us constructs his own along the way or, ultimately, on the store of his experiences, or those of others, similar to his; and so the moral universe of each of us, properly interpreted, coincides with the sum of our previous experiences, and thus represents a condensed version of our biography. The biography of my Greek was linear: that of a strong, cold man, solitary and logical, who had moved from childhood within the rigid meshes of a mercantile society. He was (or had been) open also to other aspirations: he wasn’t indifferent to the sky and the sea in his country, the pleasures of home and family, dialectic encounters. But he had been conditioned to push all this to the margins of his day and of his life, so that it did not disturb what he called the travail d’homme. His had been a life of war, and he considered cowardly and blind anyone who rejected that universe of iron. The Lager had come to us both: I had perceived it as a monstrous distortion, an ugly anomaly of my history and the history of the world, he as a sad confirmation of well-known things. “There is always war,” man is a wolf toward man: an old story. Of his two years in Auschwitz he never spoke to me.

He talked to me, instead, eloquently, about his many activities in Salonika, of the batches of goods bought, sold, smuggled by sea, or at night across the Bulgarian border; of the scams shamefully endured and those gloriously perpetrated; and, finally, of the happy, tranquil hours passed on the shore of the gulf, after the day of work, with his merchant colleagues, in certain cafés on stilts that he described with unusual abandon, and of the long conversations that were held there. What conversations? About money, about customs, about freight charges, naturally; but also about other things. What is to be understood by “knowledge,” by “spirit,” by “justice,” by “truth.” What is the nature of the fragile tie that binds the soul to the body, how it is established at birth and released at death. What is freedom, and how to reconcile the conflict between freedom of the spirit and fate. What follows death, too; and other grand Greek things. But all this in the evening, of course, when the trafficking was done, with coffee or wine or olives, a brilliant game of intellect among men active also in idleness: without passion.

Why the Greek told me these things, why he confessed to me, isn’t clear. Maybe, in front of me, who was so different, so foreign, he felt alone, and his conversation was a monologue.

The next morning, we would have to leave. For dinner each of us had two of the eggs acquired in the morning, saving the last two for breakfast. After the events of the day, I felt much “younger” compared with the Greek. When it came to the eggs, I asked if he knew how to distinguish between a raw egg and a hard-boiled one from the outside (you spin the egg rapidly, on a table, for example; if it’s hard it spins for a long time, if it’s raw it stops almost immediately): it was a minor skill I was proud of. I hoped that the Greek didn’t know it, and so I would be able to rehabilitate myself in his eyes, if in a small way.

But the Greek looked at me with his cold, wise serpent’s eyes: “What do you take me for? Do you think I was born yesterday? You think that I never dealt in eggs? Come on, tell me some item I’ve never dealt in!”

I had to make my retreat.

We left the following morning, at dawn (this is a tale interwoven with cold dawns), with Katowice as our goal: it had been confirmed that there actually existed various transit centers for scattered Italians, French, Greeks, and so on. Katowice was only about eighty kilometers from Kraków: little more than an hour by train in normal times. But in those days there wasn’t a twenty-kilometer section of track without a transfer, many bridges had been blown up, and because of the terrible state of the line the trains proceeded very slowly during the day and at night didn’t run at all. It was a labyrinthine journey, which lasted three days, with nighttime stops in places ridiculously far from the junction between the two ends: a journey of cold and hunger, which brought us the first day to a place called Trzebinia. Here the train stopped, and I went out onto the platform to stretch my legs, which were stiff with cold. Maybe I was among the first dressed in “zebra stripes” to appear in that place called Trzebinia: I was immediately at the center of a dense circle of the curious who questioned me volubly in Polish. I answered as well as I could in German; and in the middle of the group of workers and peasants a middle-class man came forward, in a felt hat, with eyeglasses and a leather portfolio in his hand—a lawyer.

He was Polish, he spoke French and German well, he was polite and kind; in short, he possessed all the qualities that enabled me finally, after the long year of slavery and silence, to recognize in him the messenger, the spokesman from the civilized world—the first I had met.

I had an avalanche of urgent things to tell the civilized world, my own but belonging to everyone, things of blood, things that, it seemed to me, would shake every conscience to its foundations. The lawyer really was polite and kind: he questioned me, and I spoke dizzily of my so recent experiences, of Auschwitz, nearby and yet, it seemed, unknown to all, of the massacre I alone had escaped, everything. The lawyer translated into Polish for the public. Now, I did not know Polish, but I knew how to say “Jew,” and how to say “political”; and I quickly realized that the translation of my account, although heartfelt, was not faithful. The lawyer described me to the audience not as an Italian Jew but as an Italian political prisoner.

I asked for an explanation, surprised and almost offended. He answered, embarrassed, “C’est mieux pour vous. La guerre n’est pas finie.” The words of the Greek.

I felt the warm wave of feeling free, of feeling myself a man among men, of feeling alive, recede into the distance. I was suddenly old, wan, tired beyond any human measure: the war isn’t over, war is forever. My listeners trickled away; they must have understood. I had dreamed something like that, we all had, in the Auschwitz night: to speak and not be listened to, to find freedom again and remain alone. Soon, I remained alone with the lawyer; after a few minutes, he, too, left me, apologizing urbanely. He urged me, as the priest had, to avoid speaking German. When I asked why, he answered vaguely, “Poland is a sad country.” He wished me good luck and offered me some money, which I refused; he seemed to me moved.

The locomotive whistled its departure. I got back in the freight car, where the Greek was waiting for me, but I didn’t tell him what had happened.

We left Szczakowa the next day, for the last stop on the journey. We reached Katowice without incident; there really did exist a transit camp for Italians, and one for Greeks. We separated without many words; but at the moment of farewell, in a fleeting yet distinct way, I felt a solitary wave of friendship move in me toward him, veined with faint gratitude, contempt, respect, animosity, curiosity, and regret that I wouldn’t see him again.

FERRARI

Recidivists were rare, with the single notable exception of the Ferrari. The Ferrari, to whose name the article was added because he was Milanese, was a marvel of inertia. He was part of a small group of common criminals, formerly detained in the San Vittore Prison, who in 1944 had been offered the choice between prison in Italy and work in Germany, and who had chosen the latter. There were about forty, almost all thieves or fences; they were a colorful, rowdy, self-contained microcosm, a perpetual source of trouble for the Russian Command.

But the Ferrari was treated by his colleagues with open contempt, and was thus relegated to an enforced solitude. He was a short man of around forty, thin and yellow, almost bald, with an absent expression. He spent his days lying on his cot, and was an indefatigable reader. He read whatever came to hand: Italian, French, German, Polish newspapers and books. Every two or three days, during the examination, he said to me, “I finished that book. Do you have another to lend me? But not in Russian, you know I don’t understand Russian well.” He wasn’t a polyglot; in fact, he was practically illiterate. But he “read” every book just the same, from the first line to the last, identifying with satisfaction the individual letters, pronouncing them in a whisper, and laboriously reconstructing words, whose meaning he didn’t care about. To him it was enough: the way, at different levels, others find pleasure in doing crossword puzzles, or solving differential equations, or calculating the orbits of asteroids.

So he was a singular individual, and his story confirmed it. He willingly told it to me, and I repeat it here.

“For many years I went to the school for thieves in Loreto. There was a mannequin with bells and a wallet in his pocket. You had to get the wallet out without the bells ringing, and I never succeeded. So I was never authorized to steal; they had me act as a lookout. I was a lookout for two years. You don’t earn much and you’re at risk. It’s not a nice job.

“I racked my brains, and one fine day I thought that, license or not, if I wanted to earn my bread I had to set off on my own.

“There was the war, the evacuation, the black market, a crowd of people on the trams. It was on the 2, at Porta Lodovica, because around there no one knew me. Near me there was a lady with a big purse; in her coat pocket, you could feel by touch, was the wallet. I got out the saccagno, very slowly . . .”

I must here insert a brief technical aside. The saccagno, the Ferrari explained to me, is a precision tool that you get by breaking in two the blade of an ordinary razor, freehand. It’s used to cut purses and pockets, so it has to be very sharp. It’s also used occasionally, in matters of honor, to disfigure; and that’s why people with scarred faces are called saccagnati.

“. . . slowly, and I started to cut the pocket. I had almost finished when a woman, not the one with the pocket, but another one, started shouting, ‘Stop thief, stop thief.’ I wasn’t doing anything to her, she didn’t know me, and she didn’t know the one with the pocket. She wasn’t even from the police, she was someone who had nothing to do with it. The fact is, the tram stopped, they caught me, I ended up in San Vittore, from there to Germany, and from Germany here. You see? That’s what can happen if you take the initiative.”

From then on, the Ferrari had taken no initiative. He was the most submissive and most docile of my clients: he immediately stripped without protesting, he presented his shirt with the inevitable lice, and the morning after submitted to the disinfection without acting like an offended prince. But the next day the lice, who knows how, were there again. He was like that: he took no initiatives, he put up no resistance, not even to lice.

• • •

THE MOOR OF VERONA

It was sad to be within the four walls while outside the air was full of spring and victory and from the nearby woods the wind brought stirring odors of moss, of new grass, of mushrooms; and it was humiliating to have to depend on my companions even for the most elementary needs, to get food from the dining room, to get water, in the first days even to change position in the bed.

There were about twenty in the dormitory, including Leonardo and Cesare; but the biggest of them, the most remarkable, was the oldest, the Moor of Verona. He must have been descended from a race tenaciously bound to the earth, since his real name was Avesani, and he was from Avesa, the washermen’s neighborhood of Verona celebrated by Berto Barbarani. He was more than seventy, and it showed: he was a large, rugged old man, with the skeleton of a dinosaur, tall and straight in the hips, and

still as strong as a horse, although his gnarled joints had stiffened with age and toil. His bald head, nobly convex, was surrounded at the base by a crown of white hair; but his gaunt, wrinkled face had a jaundiced color, and his eyes, flashing violently yellow and veined with blood, were sunk under enormous arched eyebrows, like ferocious dogs at the back of their dens.

In the Moor’s skeletal yet powerful breast, a gigantic but undefined anger boiled without respite: a senseless anger against everyone and everything, against the Russians and the Germans, against Italy and the Italians, against God and men, against himself and against us, against the day when it was day and the night when it was night, against his fate and all fates, against his trade, although it was in his blood. He was a mason; he had laid bricks for fifty years—in Italy, in America, in France, then in Italy again—and finally in Germany, and every brick was mortared with curses. He cursed continually, but not mechanically, he cursed methodically and deliberately, bitterly, stopping to look for the right word, often correcting himself, and racking his brains when he couldn’t find the right word; then he cursed the curse that wouldn’t come.

It was clear that he was besieged by a hopeless senile dementia, but there was grandeur in his dementia, and also force, and a barbaric dignity, the trampled dignity of a beast in a cage, the same that redeems Capaneus and Caliban.